I’ve recently revisited C.S. Lewis’ Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (1955), which now strikes me as perhaps his best book, a spiritual autobiography with plenty to offer both Christian and non-Christian readers. The title comes from a William Wordsworth poem and indeed Surprised by Joy seems to me like a 20th century prose equivalent of Wordsworth’s epic poem The Prelude, or Growth of a Poet’s Mind; both are histories of imaginations.

Lewis uses the term ‘joy’, a very rough translation of the German Sehnsucht (longing, yearning, nostalgia, desire), to refer to the most profound kind of imaginative-aesthetic experience, “that of an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction.” He describes three early glimpses of joy in the book’s first chapter. When Lewis was a very young child, his older brother Warren built a small diorama of a forest — “the lid of a biscuit tin which he had covered with moss and garnished with twigs and flowers” — that awakened Lewis to both the beauty of nature and beauty itself and continued to grow and blossom in his memory. “As long as I live,” Lewis writes, “my imagination of Paradise will retain something of my brother’s toy garden.”

At the age of seven or eight Lewis read Beatrix Potter’s picture book The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, which in his words “troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn.” Finally, young Lewis read a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem inspired by Norse mythology which, “like a voice from far more distance regions,” gave him a glimpse of another world and started a lifelong love of myth:

I knew nothing about Balder but instantly I was uplifted into huge regions of northern sky, I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale and remote) and then, as in the other examples, found myself at the very same moment already falling out of that desire and wishing I were back in it.

Of course Surprised by Joy inspired reflection on my own youthful experiences of joy, on the moments that opened new doors for my youthful imagination. Writing about these experiences creates an obvious problem — they are, by definition, difficult if not impossible to put into words. I’ll do my best in this essay, focusing on my experiences of cinematic joy.

On reflection I can identify two main reasons for my particular interest in film, which lead to me to work on a feature documentary and pursue an MA in Film. The first would be an intellectual appreciate of film’s history and aesthetics, a fascination with how the medium has changed over the past 130 years. The Lumiere actualities and their glimpses of a living, moving 19th century; the affinity between cinematic style and older visual art media; the possibility of harmony, counterpoint or dissonance between image and soundtrack; the impact of sound, color, visual effects and digital cameras; the unending push-pull between artistic pretension and economic necessity; film as a record of the past or as a door to fantasy worlds. All of this interested me to no end and still has me seeking out new cinematic experiences from throughout the world and throughout film’s history.

The second and much more important reason is that throughout my life I’ve had a handful of overwhelming experiences with specific films that continue to haunt me: joyful experiences in Lewis’ sense of the word.

I was certainly not the only member of my generation to grow up with Disney’s Fantasia (1940) on VHS; during the early 1990s it became the highest selling videotape of all time. I, however, did have an abnormally strong reaction to the film, which sparked a lifelong love of classical music, reignited my love of Disney when I revisited as a teenager, and continues to live and breathe in my imagination. More than once in my adult life I’ve acted as an ‘evangelist’ for this film, showing it to friends who had not seen it in many years and urging them to see and enjoy its unique alchemy of avant-garde and kitsch and, above all, its sheer spectacle.

My childhood love of dinosaurs offers only a partial explanation; I certainly enjoyed Jurassic Park (1993) and other dinosaur movies but none of them haunted me or troubled me or stirred that inner sense that Lewis wrote about.

Perhaps the best way to explain my enduring fascination with this film would be to turn to the next film that truly stabbed me with joy, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which I first saw at age ten or eleven. While Stanley Kubrick and Walt Disney are generally perceived as on opposite ends of the art-commerce spectrum, I see so much of Fantasia in the latter film; the sequence of Dr. Heywood Floyd’s flight to the moon, set to Johann Strauss II’s “Blue Danube” waltz, could almost be a segment from a hypothetical 1960s Fantasia. (Danny Peary makes this connection in Cult Movies, a book that helped shape me as a young film buff.)

“2001 is a nonverbal experience,” Stanley Kubrick told an interviewer in 1968.

I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbal pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious… I intended the film to be an intensely subjective experience that reaches the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does.

Fantasia hit me on that inner, primal, pre-verbal level of consciousness, and I can explain its effect on me as well as I can explain that of the fourth movement of Mozart’s 41st Symphony, which is to say not at all.

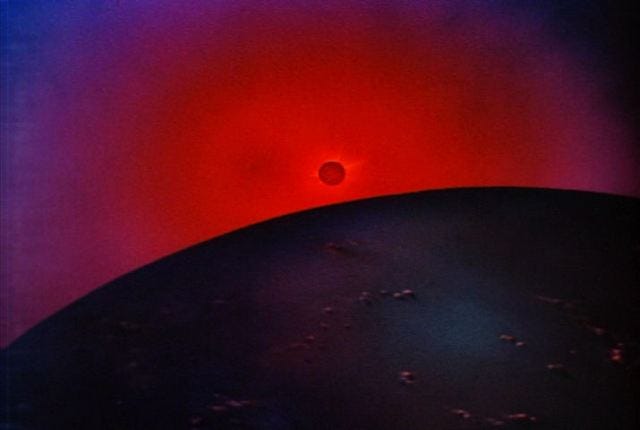

Or, to look at it from a different angle, the vast majority of the films and fiction we consume concern human beings like us, with wants, needs, aspirations and challenges we can understand. Fantasia and 2001, to a lesser extent, center the non-human. (Both films also deal with time on a non-human scale, with my favorite segment of Fantasia beginning with the emergence of single-celled life and ending with the extinction of the dinosaurs.) Disney, anthropomorphizer par excellence, devotes much of Fantasia, especially the first half, to scenes almost completely lacking characterization. Abstract shapes rise and fall, appear and disappear; lava erupts from the mouths of volcanoes and flows down to primordial seas; autumn leaves, animated into a ballet by the wind, fall from their branches to the forest floor; the sun rises through the branches of a cathedral of trees. And water flows, bubbles, eddies, forms whirlpools, crashes in waves on the shore and falls as rain or snow. Fantasia is, to use a term that seems to have fallen out of favor, almost pure cinema: music, color and motion.

Much of 2001, of course, concerns either grunting early hominids or the rogue AI HAL 9000, with unseen, unknown, perhaps unknowable aliens behind and beyond the action. And its most notorious and most psychedelic sequence, the ‘stargate,’ is, again, almost pure color, pure shape. (Now, well over 50 years after the release of 2001, these two films remain mainstream Hollywood’s farthest forays into the abstraction of modern art, with one of them coming from a name that has for decades represented everything commercial and marketable. Fantasia represents, among many other things, Walt Disney of all people deciding to get pretentious, deciding to make Art.)

2001 — and parts of Fantasia, to a lesser extent — gave me a true and somewhat uncomfortable feeling of distance, of events on a scale and at a pace beyond that of human experience or comprehension. I would now, for reasons I will explain later on in this essay, describe this feeling using the Romantic term sublime. C.S. Lewis, as previously mentioned, described his fantasy vision of Nordic myth as “cold, spacious, severe, pale and remote,” words that come very close to my experience of 2001. HAL started appearing in my nightmares, beginning, as I distinctly remember, the night after I first watched the film.

The most famous match cut in 2001 — and, in all likelihood, the single most famous cut in film history — spans millennia, linking the first ever tool, a bone club, to the most advanced, a space station orbiting earth. 24 years earlier, 2001 special effects artist Charles Staffell worked on a British film called A Canterbury Tale (1944), which includes a cut so similar as to spark decades of speculation as to whether Stanley Kubrick, Staffell or both had taken inspiration from that mostly obscure cult classic. A Canterbury Tale begins with a prelude set in medieval England, with Chaucer’s pilgrims on their journey to Canterbury Cathedral, site of the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket. One of them, a falconer, releases his falcon, which flies into the sky; the film cuts first to a fighter plane and then to a World War II soldier, played by the same actor as the falconer. In both cases, the cut across centuries emphasizes continuity as much as change: the connection between the transformative first use of technology and its subsequent transformation of Homo sapiens into a spacefaring species; the ghostly presence of Kent’s long and storied past haunting its present.

I discovered this film by accident. One day, as a UCI undergrad aged about 22, I drove to the library in order to check out a few movies to watch over a weekend. (Having an immense library of movies available for instant streaming is, somewhat paradoxically, less exciting to me than physically browsing through a much more limited selection of DVDs.) Scanning the titles, my eyes landed on A Canterbury Tale, which I picked up, perhaps due to memories of reading one of Geoffrey Chaucer’s tales in high school English class. “Everyone has heard of Canterbury,” co-director Michael Powell writes in his autobiography, “If only because they murder archbishops there.”

I can still almost see myself that night, in that dark dorm room, lit only by the cold glow coming from my laptop screen, as I watch the film for the first time and feel that stab of joy as three World War II “pilgrims” encounter history, and perhaps something more numinous, in the ancient cathedral city of Canterbury. I had a strong, immediate longing for the old, quaint, haunted, picturesque, sunlit, cloudy and sometimes sinister countryside of Kent, and for the pilgrimage site at its heart. This longing was, perhaps more than anything, for a place so shaped by and in such close proximity to the past and the people who lived there. In the words of Thomas Colpepper (Eric Portman), magistrate, gentleman farmer and self-appointed guardian of tradition,

You ford the same rivers. The same birds are singing. When you lie flat on your back and rest, and watch the clouds sailing, as I often do, you're so close to those other people, that you can hear the thrumming of the hoofs of their horses, and the sound of the wheels on the road, and their laughter and talk, and the music of the instruments they carried. And when I turn the bend in the road, where they too saw the towers of Canterbury, I feel I've only to turn my head, to see them on the road behind me.

Instead of trying to further describe my subjective experience of this film, the best illustration of its effect on me would be to simply outline the next few years of my life. As an undergraduate I applied for a Fulbright Scholarship to fund a year of postgraduate study at the University of Kent, a year in which I would analyze the World War II films of “The Archers” — Powell, Emeric Pressburger and their collaborators — in relation to the “special relationship” between the United States and United Kingdom. I ended up not receiving the scholarship but applied to and attended The University of Kent anyway, with a somewhat different angle for my thesis.

In preparation for studying A Canterbury Tale and I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), which seemed to me almost like cinematic equivalents of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner’s Romantic paintings, I took an English department course on the British Romantic movement. My professor, to my enduring gratitude, focused exclusively on the writings of the British Romantics themselves instead of on later scholarship about them. In the writings of Wordsworth and Coleridge I found an approach to the aesthetic experience that was both sympatico with what I had always felt but never put into words and a compelling alternative to academic approaches, which too often deal with a film or a book or a painting as symptom of social pathology rather than something to be experienced and enjoyed. And of course Romantic aesthetics seemed — and still seems to me — the best approach to these strange, wonderful, whimsical films.

So, having graduated I was, in Chaucer’s Middle English words, “Redy to wenden on my pilgrimage/To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,” although I was devoted not to faith but to art.

Lewis ends his book by looking back on his experiences of joy from a new perspective, seeing them as signposts pointing to “something other and outer.” In my case, A Canterbury Tale — like the old bishop’s finger signposts on the pilgrim’s way itself — pointed me towards Canterbury and its cathedral, where I had two distinct but related realizations. The first was the result, at least partially, of moving from suburban Southern California to an English city that predates the Roman Empire. From then on I knew that my life as a writer would be to a great extent about “those other people,” about their simultaneous nearness to and distance from us. History has fascinated me for most of my life but my year in a place so haunted by it helped me feel it, know it, taste it in a way which is absolutely impossible in suburban Southern California.

Second, Canterbury Cathedral’s sheer holiness, the light through its stained glass windows, the quiet of the chapels in its crypt, the echo of the organ through its cavernous space and perhaps above all the lingering presence of “the hooly blisful martir” Thomas Beckett helped start me on another journey, another pilgrimage, one that indeed began with a movie, led to my baptism at age 26 and through fits and starts still continues today.

A superb essay which reminds me so much of Susan Sontag's "Against Interpretation" where she says: "In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art."

Meaning of course not that we must switch off our brains or critical thinking, but that instead of prioritising the mechanics of the art we should prioritise the aesthetic sense of experiencing that art as a sensuous thing made up of shapes and colours and sounds.

Kent is definitely beautiful but so is much of rural England in general.

A brilliant essay. Although Fantasia hasn't been my favourite film to watch. I would happily listen to the music. Jurassic Park is my all-time favourite film; I always come back to it when I'm poorly for some reason. I haven't seen 2001, but I am intrigued by your connection between this and Fantasia. I will have to watch this soon.