Raising Ravens

Carlos Saura and the Art of Filmmaking Under Authoritarian Regimes

For me the cinema is a type of drug, an obsession.

Carlos Saura, quoted by Reuters

Spanish filmmaker Carlos Saura (1932-2023) died earlier this month after a career as a director that lasted more than sixty years and included more than forty feature films eight short films. His work, which brought him to Argentina and Mexico, ranges from neorealism to psychological thrillers, flamenco musicals, a Borges adaptation and a documentary of the 1992 Barcelona Summer Olympics. His films won a total of seven awards at the Cannes and Berlin film festivals and were nominated for three Oscars. Referring to one of Saura’s earliest films, director Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón told Variety that “there is a Spanish cinema before and after La Caza.”

“I first encountered Saura’s work by chance and in a rather strange way,” Stanley Kubrick told Spanish newspaper El Pais in 1980.

I got home quite late and turned on the television: a film in Spanish with subtitles, that I knew absolutely nothing about, and besides, I’d missed the first half hour. It was hard for me to follow and understand but, at the same time, I was convinced it was the film of a great director.

I watched the rest of the film glued to the TV set and when it was over I picked up a newspaper and saw that it was Peppermint Frappé by Carlos Saura. Later I found a copy of the film, which of course I watched from the beginning and with great enthusiasm, and since then all of Saura’s films that I’ve seen have confirmed the high quality of his work. He is an extremely brilliant director, and what strikes me in particular is the marvelous use he makes of his actors.

Saura’s obituaries have focused on two main points, his long and productive career and, possibly his most important legacy, his early work as a director of critical, subversive films during the Franco regime. The Hollywood Reporter headline, for instance, is “Carlos Saura, Spanish Director Who Lifted Country’s Cinema Amid Franco Dictatorship, Dies at 91.” The Reuters article begins with “filmmaker Carlos Saura, who led the awakening of Spain's art cinema after decades of fascist dictatorship under Francisco Franco…” The New York Times subhead reads “called ‘one of the fundamental filmmakers in the history of Spanish cinema,’ he began making movies under Franco, often hiding his messages in allegory.”

I myself discovered Saura’s work just last year, when the Criterion Channel streamed the retrospective Directed by Carlos Saura. His sixties and seventies films have a quality I often look for but rarely find: true strangeness. Just as animals in isolated environments like islands and caves have a tendency to evolve in strange directions, these products of isolated late fascist Spain make up something like their own genre, one with a uniquely uncomfortable, uniquely unsettling combination of ennui and banality with dread and eventual climactic moments of shocking violence.

Peppermint Frappé struck me as well. On one hand, it is clearly an homage to/pastiche of Vertigo (1958), telling a similar story of an obsessed, unbalanced man trying to mold a woman à la Pygmalion and Galatea into his fantasy. It has a few direct quotes of that film, including an extreme closeup of Geraldine Chaplin’s eye that recalls the Vertigo credits sequence and a climactic kiss shot by a camera circling around the male lead embracing his newly blonde object of obsession.

On the other hand, it pushes that film’s underlying fetishism even further, as seen in the pre-credits and credits sequence: hands cutting pictures of women’s faces and bodies out of fashion magazines and pasting them into the kind of scrapbook found in a police search of a serial killer’s home. Those hands belong to Julian (José Luis López Vázquez), who goes to even darker places than Jimmy Stewart’s detective. One might almost call the film the missing link between Vertigo and the more arthouse weirdness of a David Lynch film.

A more general Hitckcockianness happens in how these films imbue inanimate objects with menace. A crème de menthe cocktail, a glass and concrete modernist house, an old tin of baking soda all take on sinister aspects.

Two overlapping themes reoccur again and again in these films. First, the idea of acting itself — the characters as performers playing roles. The middle-class husband and wife in Honeycomb (1969) withdraw from the world to act out increasingly extreme psychosexual scenarios. A car crash leaves the protagonist of The Garden of Delights (1970) amnesiac and wheelchair-bound; his family tries a variety of tactics, including staging reenactments of his traumatic childhood experiences, in the hope of jolting back his memory of his Swiss bank account number. And in a truly powerful, disturbing scene, the three young sisters in Cria Cuervos (1976) put on old clothes and makeup to act out scenes from their dead parents’ marital dysfunction.

Second, as seen in all of the previous examples, the way in which traumatic formative experiences can haunt someone for a lifetime. In La Caza (1965), a rabbit hunting trip awakens memories of combat — and bloodthirst — in three Spanish Civil War veterans. In the aforementioned Peppermint Frappé, the protagonist obsesses about a woman he once saw drumming at demonstration. In Honeycomb, the bizarre and eventually deadly games begin when a basement full of old furniture and various bric-a-brac brings back the wife’s old — repressed? — memories of a traumatic childhood.

These films feel very much of a piece, cut from the same cloth, with many of the same actors — including Geraldine Chaplin, Charlie’s daughter and Saura’s muse/one-time common-law wife — and the consistent involvement of producer Elías Querejeta, who also produced The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) and The City of Lost Children (1995). Cinematographer Luis Cuadrado shot La Caza, Peppermint Frappé, Stress Makes Three (1968), Honeycomb, The Garden of Delights and Anna and the Wolves (1973); Rafael Azcona worked on the Peppermint Frappé, Honeycomb, Garden of Delights, Anna and the Wolves and Cousin Angelica (1974) screenplays; Pablo del Almo edited all of Saura’s films from La Caza to the early eighties. (In other words, Criterion’s retrospective Directed by Carlos Saura speaks to how so often references to a single film auteur are really shorthand for a larger team.)

Cria Cuervos, generally considered Saura’s best film, was made literally at the end of the Franco era and serves as a summation of a cinematic decade, weaving together the previous film’s themes of haunting by the past, obsession, repression, frustration, control, lack of control, betrayal, confinement: in other words, the various psychic costs of an authoritarian regime.

The Saura retrospective provides a perfect example of why the Criterion Channel or something like it needs to exist. In my mind, Criterion has two main functions. First, and most obviously, to preserve and make accessible the true canonical classics, the films that have truly stood the test of time: to provide a way for new audiences to discover the likes of City Lights or Seven Samurai or 8½ for themselves.

Second, the Criterion Channel exists in a media ecosystem of overwhelming abundance, of instant availability, of more options than a human being could consume in a lifetime. And a new movie or episode or piece of “content” gets released every second of every minute of every day. Of course, this cacophonous overload drowns out subtler, more challenging, more obscure and in some cases simply older works. And so, like a museum with both a permanent collection and temporary exhibitions Criterion offers retrospectives of films and filmmakers that have for whatever reason fallen under the radar. (Many worthwhile films were simply unavailable to consumers for decades.) The films of Carlos Saura, now available for rediscovery, provide a perfect example of how streaming can connect overlooked films to new audiences.

On reflection, the thread of filmmaking under authoritarian regimes runs through some of the best films I’ve seen in the past few years. And so, in memory of Carlos Saura, I present brief introductions to five films that compel and enthrall not despite but because of the almost impossible circumstances of their creation.

As anyone who’s ever worked on a movie knows all too well, the filmmaking process can be — and almost inevitably will be — long, taxing and frustrating even under much easier sociopolitical conditions. When I saw Terry Gilliam speak he compared the film director’s job to that of a captain of a sinking ship with a mutinying crew, trying to get from port to port on schedule while also simultaneously making art.

But Saura and his counterparts in other times and places were able to navigate through all this, plus very real threats of surveillance, censorship and imprisonment. To stretch Gilliam’s metaphor further, these sinking, mutinying ships also had blockaded ports and U-boats to deal with. And out of these challenges, somehow, came truly memorable films.

How? Part of it, to resort to a true cliché, is necessity’s mothering of invention. Circumstances forced the makers of the films I am about to list to improvise, to draw on inner resources, to push themselves and their colleagues into new creative places. “Sometimes restrictions get the mind going,” David Lynch writes in Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness and Creativity. “If you’ve got tons and tons of money, you may relax and figure that you can throw money at any problem that comes along. You don’t have to think so hard.”

Just as important, above and beyond all the trials of making a film in normal conditions these filmmakers made incredible sacrifices and took incredible risks to bring us these following five films — these are works that their creators truly believed in. Multiplexes and streaming services abound with pure product made by comfortable people looking to make more money, but no one would risk the wrath of the KGB for hackwork.

Les Enfants du Paradis/Children of Paradise (1945)

All discussions of this film, to quote the first sentence of Roger Ebert’s review, “begin with the miracle of its making.” An extravagant film that would have taxed a Hollywood studio at the height of its powers, Children of Paradise was made in Nazi-occupied France under the Vichy puppet government.

“Thinking about it now,” director Marcel Carné told interviewer Brian Stonehill in 1990, “it was madness to make such a film in a country lacking the bare necessities.” On the set of his previous film, Les Visiteurs du Soir (1942), he had to shoot banqueting scenes again and again because starving extras and crew members would devour the food before the lights and cameras had been set up. The production of Children of Paradise would involve even more serious challenges.

The film’s Jewish composer Joseph Kosma wrote its score while under house arrest; Jewish art director Alexandre Trauner designed its sets while living in hiding under an assumed name. (In Carné’s words, he “hid in a cabin in the middle of the forest” and built miniature model sets without ever seeing the full-sized final versions.) The French Resistance, whose leadership included one of the film’s assistant directors, outed supporting actor Robert Le Vigan as a Nazi collaborator and sentenced him to death. Le Vigan fled to Germany and Pierre Renoir — Jean’s brother — took his role. One of the film’s production directors disappeared one day, Carné would later recall.

Finally, I found out that he had run off because there were two Gestapo agents waiting for him downstairs in our second-floor studio. We had opened a garage behind the studio to make it into a costume shop, and he fled that way. If, by chance, we hadn’t, the Gestapo would have seized him.

The film that emerged from these circumstances could not be more different than Rome, Open City (1945), Shoeshine (1946) and the other pioneering shoestring neorealist films made at the same time in Italy. Children of Paradise was the most expensive French film ever made up to that point, a painstaking recreation of pre-Baron Haussmann Paris, a 190-minute two-part epic of actors, mimes, thieves, courtesans and noblemen set in theaters, cabarets, mansions and, above all, along the carnivalesque Boulevard du Crime with its street performers, sideshows, horse-drawn carriages, pickpockets and endless crowd. “Watching it,” in the words of critic Dudley Andrews, “is like losing oneself in an immense novel.”

The French Impressionists took inspiration from a genre of Japanese woodblock prints called ukiyo-e, ‘floating world,’ representations of the urban nocturnal world of sake bars, geisha houses and kabuki theaters. This film, like a Degas ballet scene or Manet’s Bar, captures the absinthe-soaked floating world of 19th century Parisian nightlife. It is, in its way, an act of subversion, an act of resistance from a team including multiple Jews and a gay director: not just an evocation but a defiant assertion of Paris Libre in in all its decadence, beauty, magnificence, sleaze and theatricality.

Let me put it another way. I’ve been to Paris several times and have absolutely experienced its food, wine, and many opportunities to encounter Art and Culture. I’ve also been pickpocketed on the banks of the Seine. More than any other Parisian film I’ve seen, Children of Paradise expresses both these realities.

Sayat Nova/The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

One of the classic old Hollywood anecdotes, set in 1915, has a producer complaining to director Cecil B. DeMille about the cinematography of his most recent movie; it is so underlit that the half of the star’s face is obscured by shadow. “It’s not underlit,” DeMille replies, “it’s Rembrandt lighting.” The previous year, of course, DeMille had directed the very first feature film ever shot in Hollywood and “Rembrandt lighting” would live much longer than his early fit of artistic pretention. In other words, the post-Renaissance western artistic tradition, with its focus on two-dimensional representations of figures in three-dimensional space, has been part of American cinema’s visual DNA since almost the very beginning. When we talk about the look of midcentury American film noir, for instance, we use the Italian word chiaroscuro — a painting term from Renaissance Italy, a term that Leonardo da Vinci would recognize — to describe the genre’s contrasts of bright whites and deep black shadows.

For well over a century, Hollywood and international filmmakers have used a variety of techniques to create their own versions of Renaissance painting’s illusion of volume-filling figures in real space: light sources casting shadows, color, shallow focus, deep focus, handheld cameras and Steadicams literally moving through space, the cyclical reoccurrences of 3d.

The Color of Pomegranates has roots in different soil. If Hollywood films — and films of the western world in general —look like oil paintings, then this film looks like Mughal or Persian miniatures and has their flat patterns of gemlike color. In it you’ll find no montages, no establishing shots, no point of view shots, no alternating closeups of over-the-shoulder shots of characters in conversation, no zooms in or out, no handheld cameras, indeed absolutely no camera movement whatsoever. Director Sergei Parajanov once described it as not so much a film as a series of Persian miniatures and that is absolutely what The Color of Pomegranates is — a series of evocative tableaux vivants, rich in color and just as rich in Armenian architecture, textiles, costume and music. It tells, in its unique visual language, the life story of the 18th century Armenian poet-troubadour Harutyun Sayatyan, who gained the epithet Sayat-Nova, King of Song.

As with the films of Carlos Saura, this use of symbolism and allegory represents something more/other than arthouse pretention: in this case, an assertion of Armenia as not just another Soviet Socialist Republic but as a country with its own unique identity, culture and history. It opens, for example, with crimson pomegranate juice staining a white tablecloth, the stain forming the shape of premodern Armenia in a cryptic getting-past-the-censors reference to the Armenian genocide and the decades of oppression that followed it. That is just the first and perhaps the most obvious symbol in a film of symbols, which I invite you to discover for yourself — as much as any other film I’ve seen, The Color of Pomegranates evades verbal description in its success as a pure audiovisual experience.

Like his contemporary Andrei Tarkovsky, Parajanov had, in the words of film historian Ian Christie, “committed the crime of creating autonomous aesthetic worlds that pointed to no clear communist morals.” Soviet censors changed the title from Sayat Nova to The Color of Pomegranates and removed all references to Sayat Nova from intertitles and dialogue on the supposed grounds of historical inaccuracy. (Also at play, in all likelihood, was the intent to blunt an expression of specifically Armenian national identity.) A reedited version was released in every Soviet Socialist Republic outside of Armenia: dialogue and intertitles translated into Russian, scenes rearranged, religious imagery excised. In Moscow, Christie writes,

it was seen as expressing a new version of the ‘formalism’ that had been labeled anti-Soviet in the thirties, on the grounds of being ‘unintelligible to the masses.’ And in 1969, a general crackdown on dissident artists was under way, as Leonid Brezhnev’s hard-liners sought to rein in the relaxation that had created a thaw under Nikita Khrushchev earlier in the decade.

After his criticism of the Soviet government attracted the notice of the KGB, Parajanov was arrested in 1973 and spent the next four years in prison; freed in 1977, he was forbidden from making films and reimprisoned for ten months in 1982. He resumed his filmmaking career under glasnost in 1985 before dying of cancer in 1990.

This story does have something approaching a happy ending. For decades, the only versions of this film available outside the USSR or its successors were low quality bootlegs of the censored Russian-language version. In 2014, the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project collaborated with Italy’s Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrova to restore the original Armenian version of the film: to get as near as possible to the filmmakers’ original intent.

So now anyone with streaming video can have a truly unique cinematic experience, one that Film Foundation founder Martin Scorsese has aptly described as “like opening a door and walking into another dimension.”

Cria Cuervos (1976)

One aspect of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) that struck me when I revisited last year was how the first half so immerses the viewer in the desert as to make its denouement, Lawrence’s ‘return to civilization,’ seem truly alien. After that epic of camels, riders, sand dunes, Bedouin tents, heat, thirst, war and life in extremis the British headquarters at Cairo — marble floors, Englishmen in uniform, fountains, a green pool table and glasses of gin & tonic at the officer’s bar — seem as bizarre, as surreal as any science fiction planet in cinema. The end of Cria Cuervos accomplishes something similar.

Child actress Ana Torrent — who you might know from The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) — plays one of three young sisters who lose first their mother and then their father and find themselves under the ‘care’ of a domineering aunt. Geraldine Chaplin plays both the girl’s mother, who lives on after her death as a memory/dream/ghost/hallucination experienced by her daughter, and the daughter herself as an adult reflecting on her troubled childhood. (The Hitchcockian model is thus not Vertigo but Rebecca.)

It is not a decaying gothic mansion or abandoned castle, its rooms are not covered in cobwebs or decorated with portraits of malevolent ancestors and no ghostly moaning or rattling of chains echoes through its halls but nonetheless the house in Cria Cuervos is one of cinema’s great haunted houses. The film is confined to this house for most of its runtime and by layering flashbacks, hallucinations, fantasies and much later adult reminiscences of these childhood events creates a location where time does not flow so much as congeal. After 100 claustrophobic minutes of gloom and neglect, the sisters’ traumatic summer vacation ends and they leave the house to go to school, walking down a loud, crowded modern Madrid street that seems like a completely different world.

Without exception, every review of the film you’ll ever read will interpret all of this as an allegory of the fall of Franco’s regime. Production began in summer 1975, when Francisco Franco lay dying of Parkinson’s disease; he hung on until November and Saura would later joke that Franco’s lingering death gave him plenty of time to buy the celebratory champagne. Released in January 1976, only two months after Franco’s death, Cria Cuervos resonated with Spanish audiences, finishing sixth on the annual box office charts. But it remains a classic by speaking to a much broader range of human experience than its original sociopolitical circumstances.

Discussing the film in an interview, Saura described childhood as “of the most terrible parts in the life of a human being.” As a child, he continued,

you've no idea where it is you are going, only that people are taking you somewhere, leading you, pulling you and you are frightened. You don't know where you're going or who you are or what you are going to do. It's a time of terrible indecision.

Many films, some of them absolute masterpieces, celebrate the curiosity and wonder of childhood but this one expresses childhood’s boredom, vulnerability, lack of agency, the way that a child’s magical thinking can go down truly dark mental corridors, childish viciousness untempered by adult rationality and sheer claustrophobia. Like prisoners, the three sisters engage in repetitive behaviors: lazing around in bed, listening to the same song over and over again, playing dress up, doing anything to use up some of the abyss of time that extends before them. (This gives it a truly contemporary resonance, as I’ve seen very few films that feel so much like the lethargy and monotony, laced with anxiety, of life under lockdown.)

But that ending has the uncertainty and sense of possibility of the first day of a Year Zero.

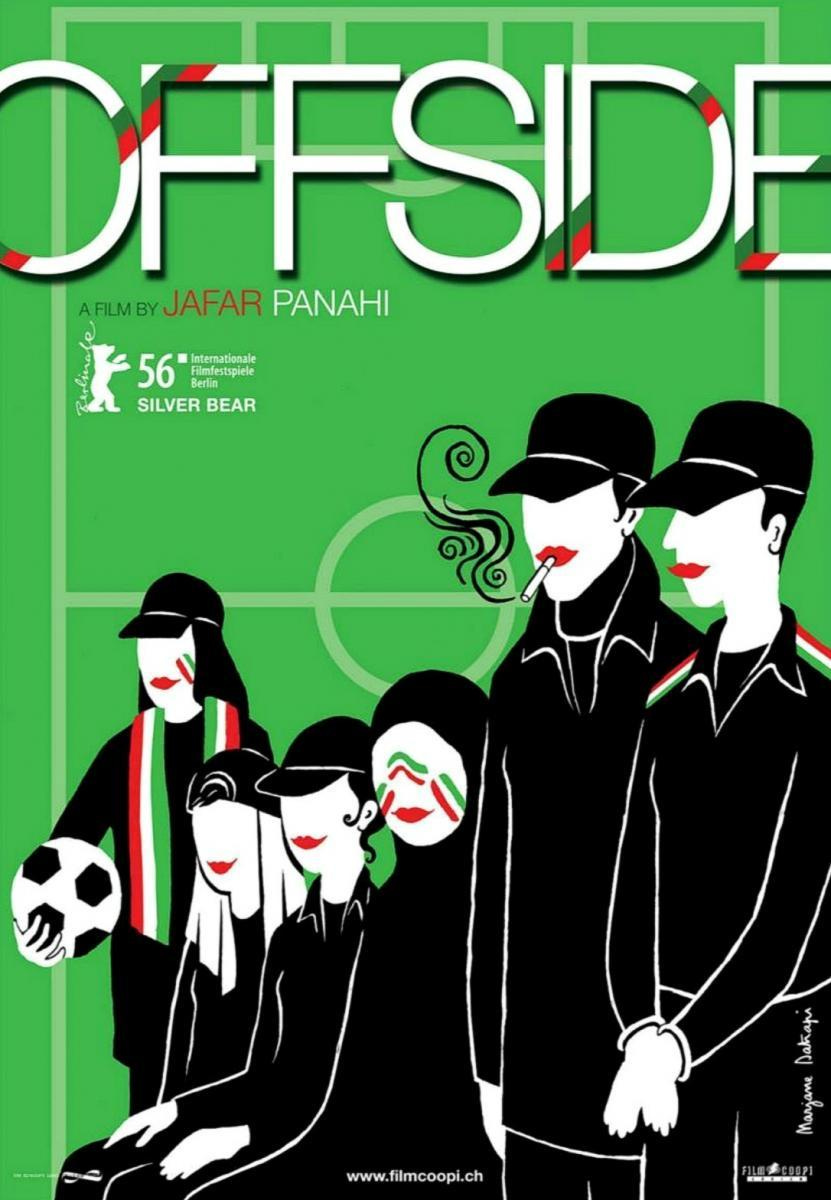

Offside (2006)

On February 4th, the Iranian government released filmmaker Jafar Panahi from his second prison term after a multi-day hunger strike. The protégé of Iran’s most internationally renowned filmmaker, the late Abbas Kiarostami, Panahi directed his first feature film in 1995. Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance banned his third film, The Circle (2000) as “offensive to Muslim women” and has banned each of his subsequent films. A supporter of the Iranian Green Movement, Panahi was first arrested and imprisoned in March 2010. Convicted of "assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic," Panahi was sentenced to six years in the notorious Evin Prison, to be followed by house arrest and a twenty-year ban on filmmaking, giving interviews and international travel. Panahi was arrested and imprisoned again in July of last year.

Despite all this, Panahi has continued to make films and has directed five features since his 2011 arrest. Part of his documentary This Is Not a Film (2011) was shot on an iPhone; as reported by the New York Times, the film was “smuggled to France on a USB thumb drive that was hidden inside a cake.” Panahi’s recent arrest prevented him from attending the Venice Film Festival premiere of his most recent film, No Bears (2022), which won the festival’s Special Jury Prize.

Considering recent events, the best entry point into Panahi’s work is Offside (2006), which is currently streaming on Amazon Prime and other services. The plot concerns a group of teenaged Iranian girls who disguise themselves as boys in order to see the Iranian national men’s soccer team play at Azadi Stadium. Like many other aspects of Iranian life, soccer is strictly sex-segregated —to quote the film’s trailer, “in Iran, women are officially banned from men’s sporting events.”

Offside was shot guerrilla-style, with a handheld camera and non-professional actors, at an actual World Cup qualifying match between Iran and Bahrain. Panahi and cowriter Shadmehr Rastin wrote two versions of the ending depending on which team ended up winning. (Iran beat Bahrain 1-0.) “We ran into many obstacles making this film,” Panahi told the Parsi Times in 2006.

five days before the end of the shoot, a newspaper published an article stating I was directing a new film. The military immediately gave orders to interrupt the shoot. We were instructed to bring them our rushes to be verified. I immediately announced to the official in charge of cinema in Iran that this was out of the question, and that I would not allow a single soldier during the final days of the shoot. Luckily, there were only a few scenes left to shoot, inside a minibus, so we just left the military zone and continued filming sixty kilometers outside of Tehran.

A serious social critique, Offside is also a satire and laugh-out-loud funny at times, especially a scene that begins with an attempt to protect one of the teenaged girls’ modesty by covering her face with a headshot of an Iranian footballer; after some persuasion her guards take her to use a men’s bathroom that ends up having as many unwelcome visitors as the Marx Brothers’ stateroom in A Night at the Opera (1935).

The film is deeply critical of the Iranian government and of coursed banned in that country but one of its major strengths is its nuance. At the stadium, the front-line enforcers of Iran’s gender segregation are not jackbooted thugs or sinister secret policemen but college-aged boys from the country, completing their mandatory military service and somewhat overwhelmed by Tehran and by their responsibilities. Indeed, the boundaries between the two groups begin to break down over the course of the film. Confined to what can only be described as a holding pen, the girls can hear the crowd inside the stadium but cannot see the game; the guards begin giving an impromptu play-by-play commentary.

Similarly, it would have been easy, expected, obvious for the film to depict soccer games as numbing, distracting 21st century bread and circuses. But the film ends with something more nuanced and, in my personal experience, more accurate: how sports fandom can create happiness and connections between people, even in the most trying of times.

A Touch of Sin (2013)

Since before I was born it has been almost de rigeur for mainland Chinese arthouse and international film festival hits to be banned in their home country: The Horse Thief (1986); Ju Dou (1990); Raise the Red Lantern (1991); The Blue Kite (1993); Farewell My Concubine (1993); Beijing Bicycle (2001); Petition (2009). Some of these bans have been lifted, some have not. The Chinese government continues to censor every form of media with increasing cooperation from western megacorporations.

A Touch of Sin director Jia Zhangke has a wealth of experience with Chinese government censorship. “My films are made entirely outside the system,” he told The Guardian in 2003 when discussing Unknown Pleasures (2003), a picture of the isolation and alienation of China’s one-child policy generation.

They have not gone through the censorship process, so they have not been approved by the Censorship Bureau. If you want to make films like mine, and the way I want to make them, you have to do it underground.

Zhangke began his filmmaking career in 1995 and has directed more than a dozen feature films. A Touch of Sin, which won the Best Screenplay Award at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, is his biggest hit in the western world and for good reason. An anthology of four stories, each based on real-life Chinese crimes and scandals, A Touch of Sin presents a Chinese society coming apart at the seams, a volcano of corruption, resentment and abuse that erupts again and again into violence.

Its title evokes that of the classic Taiwanese-Hong Kong martial arts epic A Touch of Zen (1971) in order to contrast the pettiness and brutality of modern China with that film’s tale of heroism and spiritual enlightenment. It is a doubly ironic title as its China has much, much more than a touch of sin — it is immersed in sin, soaked in the sin not trickling but torrenting down from the CCP.

Instead of summarizing these plots I will briefly describe two aspects of it that have stayed with me. First, the film’s multiple storylines offer a kind of travelogue of 21st century China, from Shanxi — not Shaanxi — Province in the north to Chongqing, and Guangdong and Hunan provinces in the south. If you’ve ever been to China, you know that despite being the world’s most populous country it has incredible wide-open spaces, truly magnificent landscapes, rivers, deserts and, above all, the mountain ranges that have inspired painters for well over a millennium. In A Touch of Sin this grandeur in the background (well-photographed like the rest of the film) provides an ironic counterpoint to the petty, vicious actions in the foreground.

Second, it has one of the great 21st century film endings, a perfect moment of pitch-black irony. After more than two hours of corruption, revenge, murder and suicide, the character of Xiaoyu (Zhao Tao), last seen blood-soaked and wielding a knife, interviews for a factory job. Her prospective employer says something like “I know you you’ve had your problems in the past” and she with something along the lines of “I’ve put all that behind me now.”

Like Panahi, Jia Zhangke has continued working regardless of censorship or possible government reprisals. “Instead of paying attention to what can be made and what can’t be made based on the government’s ambiguous standards, it’s more important to think about what you want to make,” he told IndieWire in 2019.

As a filmmaker, the most important thing is that I make the film I want to make without paying attention to what the other parts of the society, the government, or the market tell me can or can’t be made.

The title of Cria Cuervos comes from an old Spanish proverb, “cría cuervos y te sacarán los ojos:” raise ravens and they’ll peck your eyes out. Carlos Saura’s career lasted much longer than Francisco Franco’s; Vichy and the USSR are long dead. But today’s regimes are raising new generations of ravens, just as old Athens raised that stinging gadfly, Socrates. So, in memory of Saura, consider watching one of these films, which while not beaks and claws certainly represent the croaks of approaching ravens.

Absolutely superb survey of some films I've seen and some I haven't. Even though I live in Spain I've never seen a Saura film. I think it's because I have a resistance to anything the "Spanish Cultural Elite" likes to recommend to itself.

In recent years lots of earnest culture types have gone on and on about him and I developed an instinctive distaste for this kind of "we decided he's good now" filmmaker. My taste tended toward the radically scabrous satire of Berlanga, whom I thought of as a kind of Buñuel descendent.

But your comments make me think I've misjudged things, so I'll give him a try.

Very much agree with your remarks on Criterion, but I've heard also that the Mubi streaming service does a good job on similar lines.

I hold Carlos Saura so dear. What a human, what a filmmaker.