Fare forward, travellers! Not escaping from the past

Into indifferent lives, or into any future;

You are not the same people who left that station

Or who will arrive at any terminus…

Fare forward, you who think that you are voyaging;

You are not those who saw the harbour

Receding, or those who will disembark.

T.S. Eliot, “The Dry Salvages,” Four Quartets

I had in a sense visited England many times before my plane landed at Heathrow, starting very young with “London Bridge is Falling Down” and Mary Poppins on VHS, encased in its big white plastic Disney box. Disneyland’s Fantasyland offered and continues to offer plenty of ye olde Englishness alongside its theme park adaptations of movie adaptations of German Märchen and French Contes des fées. A guest who enters Fantasyland through a miniature reproduction of Neuschwanstein Castle, for example, finds himself or herself in front of a carousel named after that most elusive and evocative of Britons, King Arthur; a particularly luck child can pull a sword from a nearby plastic stone. On the rides themselves one can fall down the rabbit hole to wonderland, drive a flivver from stately Toad Hall to cobblestoned Victorian streets, or, in the words of the classic Peter Pan’s Flight poster, “sail over moonlit London to Never Land aboard a pirate galleon.”

But my most important encounters with England, especially London, occurred in books. Four children finding refuge from the Blitz in a country house with a magic wardrobe; Holmes and Watson taking a hansom cab from 221B Baker Street to the scene of the crime; Martian war machines descending on the home counties; Mr. Jekyll returning to his lair after a night of debaucheries; Scrooge walking home through the cold and fog to find “not a knocker — but Marley’s face” at his front door; young William Wordsworth astonished by the “parliament of monsters” at Bartholomew Fair; the King’s Men performing immortal plays in their thatch-roofed theater surrounded by taverns, brothels and bear-baiting pits, as described in the introductions to ever play in the Folger Shakespeare Library. On the flight over I listened to an audiobook of Great Expectations, sympatico with Pip’s thoughts on his own voyage to London: “henceforth I was for London and greatness.”

The United States and United Kingdom have, in Churchill’s famous words, a special relationship, and, from an American perspective, a large part of that relationship is Britain’s constant presence as an older culture influencing our own, as a deep-rooted tree of which we are a branch. “Our schoolteachers,” writes Saul Bellow of his Chicago childhood in the twenties and thirties,

were something like missionaries. They earnestly tried to convert or civilize their pupils, the children of immigrants from every European country. To civilize was to Americanize us all, and to Americanize was in no small part to Anglicize. We were to learn what America owed to English history, English law, and English literature.

While my education, seventy years later, involved very little English history or English law, English literature remained the gold standard in English and Language Arts classes. From elementary school through community college I was assigned many more British books than American books: John Steinbeck, the American west’s only representative, outnumbered by east coast writers and of course by Shakespeare, Orwell, Wilde, Dickens, Stevenson, Mary Shelley, William Golding and D.H. Lawrence.

The special relationship has another aspect for members of my generation, who are for the most part the children of younger baby boomers. For many of us, myself included, the discovery of our parent’s music collection marked an important moment in the development of our taste, with Who’s Next or Led Zeppelin IV or Revolver or The Dark Side of the Moon as the gateway into a new musical world. Those great old British bands had a mystique, a personality, a color distinct from that of contemporary bands; “millennials” seem to have an unusual ability to get nostalgic about other people’s pasts. As a young hipster, a decade ago, I dug through used record store bins for new Yes or Faces or Deep Purple albums to add to the collection and was not alone in doing so.

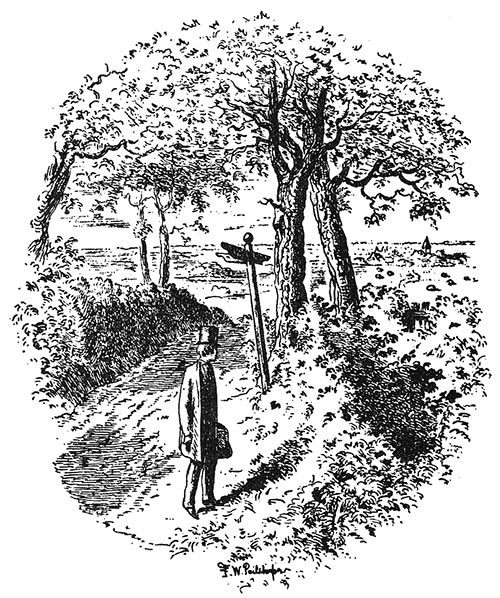

On reflection, these albums added quite a bit to our inner Englands, filling out our mental maps with placenames like Abbey Road, Muswell Hill, the Isle of Wight, introducing terms like roundabout and afternoon tea. Then as now, Leeds — a city with almost 2 million people in its urban area — is in my mind primarily where The Who recorded their classic live album, Brighton where Jimmy has his existential crisis in Quadrophenia. Thus I brought an imaginary England with me to the real England, a heterogenous world of village greens, cathedral spires, glowing fires in snow-covered inns, disillusioned mods on gray beaches, steam trains puffing through the countryside, gaslights glaring through foggy streets, pirate radio stations, intricate murders at gothic manors and castles surrounded by dark green forests.

It first hit me that I was really leaving when I looked back from the LAX escalator and saw my mom and dad standing below, tears in her eyes. I looked at them, from the escalator and the security checkpoint line, until they were no longer in view. I wouldn’t see them, or be back in the states, for another year.

After I passed through security I had the sensation of being in a timeless, placeless place. While in England I rediscovered C.S. Lewis — as an essayist, literary critic, and Christian apologist, whereas my younger self knew him as a children’s novelist — and in the first Narnia book, if I remember correctly, the characters enter Narnia through “the wood between the worlds.” I felt like I was in between worlds in that terminal.

I ordered a White Russian at the bar because of The Big Lebowski and started talking hockey with a Canadian sitting next to me. He was from Nova Scotia and told me about what a great guy Sidney Crosby is and how involved he is in the community. He also had some less-than-nice things to say about a few other players he had met, and about the state of Canadian junior hockey in general.

Sometimes you encounter a book or an album or a film at just the right moment in your life where it provides just what you need at that point; I had that experience with Nathanael West’s novel Miss Lonelyhearts in that terminal. I’d really tried to seriously get into American literature that summary, reading Emerson and Mark Twain beyond Tom Sawyer and Sherwood Anderson beyond Winesburg, Ohio, and I decided to read one last American book while still on American soil. I finished the slim novel in an hour or so waiting for my flight and, as cliched as it sounds, the title character’s loneliness and desire to help other people spoke to me as I waited to begin this new chapter of my life.

On the flight over I sat next to an elderly British couple who told me, with a certain amount of local pride, that they lived by the very last Tube stop, the end of the line, on the outskirts of London in Essex. I told them that it was my first time in England and that I would be study at the University of Kent. Their eyes lit up when I told them my dissertation topic and the husband told me in his Cockneyish accent — I would later discover a whole world of British accents — that they had grown up watching Powell & Pressburger films (and Ealing Comedies as well.) After landing, I had a nice conversation with another American student in the customs line. We promised to meet up again later in London but never did.

Customs and Immigration, fortunately, were not as much of an ordeal as I had feared and I was soon on my way, riding the Tube for over an hour from Heathrow to St. Pancras/Kings Cross. As a native Southern Californian, I have not had much occasion to ride trains — except, of course, on the Disneyland Railroad — or light rail, something that would quickly change during my stay in England. I remember being tired and jetlagged, half dreaming, watching stations and rows and rows of identical housings passing by like a procession. (In hindsight, a much more efficient route from Heathrow to central London is the 15-minute Heathrow Express to Paddington Station, the famous bear’s namesake.)

I arrived at St. Pancras Station, which I will discuss later, and walked across the street with my baggage to the Premier Inn. Rain fell, introducing the vagaries of English weather. (“Sitting in an English garden, waiting for the sun.”) After checking in and dropping off my bags I crossed the street again and walked down the crowded sidewalk to the British Library. Unlike St. Pancras next door, a cathedral of a train station that, without fail, signifies London and “Englishness,” the British Library is a less-than-impressive structure on the outside; you wish it could be a white marble Neoclassical temple like the British Museum or National Gallery. I was very tired but I do have strong memories of Jane Austen manuscripts and original Beatles lyrics.

Afterwards I visited my first British pub, The Skinners Arms on Judd Street, and had two other firsts: my first bangers & mash and my first real cask ale, a Shepherd Neame Spitfire. In all honesty, my first impression of British pub-going was of a lack of seating relative to the number of customers and the ensuing challenge of finding a table. (This is a deliberate business strategy called High Volume Vertical Drinking, where standing up with a drink constantly in hand encourages customers to drink faster.) I did manage to find a table and, beer in hand, discover the true joy that exists in a wood-paneled British pub with casks in the cellar. There is, strangely, no English-language word for this quintessentially English experience; the best way to describe it would be with the German word Gemütlichkeit or the Danish Hygge, or by referencing George Orwell’s ideal pub in his essay “The Moon Under Water.”

I returned to my hotel room early and slept the unworried sleep of someone with few obligations and an entire country waiting to be discovered.

So interesting hearing about a sort of fantasy Britain from books and music. I suppose I have the same thing with America - though I do hope to go sometime soon! It's different for me to see through the eyes of entering England the first time through public transport, but I had a similar experience visiting Germany last year.

I enjoyed this piece a lot Robert.

The parts about you being in the liminal space of the airport were very interesting. I especially liked your observation that

—“ I felt like I was in between worlds in that terminal.”— that is a good point, as airports do seem to have a sort of ‘nowhere/transitory’ feel to them.

I also really enjoyed the way you told the story of your journey, it flowed in a way that had me keen to follow.