The key to progress has been the proliferation of the small vineyard making a particular wine from a particular grape grown on a particular piece of earth.

Roy Andries de Groot, The Wines of California, The Pacific Northwest and New York

My Larousse French-English Dictionary defines terroir as simply ‘soil’ or ‘country’ (as in ‘countryside’). Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson offer a much more expansive definition in the sixth edition of The World Atlas of Wine: “There is no precise translation for the French word terroir,” they write.

It embraces the soil itself, the subsoil and rocks beneath it, its physical and chemical properties and how they interact with the local climate, the macroclimate of the region, to determine both the mesoclimate of a particular vineyard and the microclimate of a particular vine. This includes for example how quickly a patch of land drains, whether it reflects sunlight or absorbs the heat, its elevation, its degree of slope, its orientation to the sun, and whether it is close to a cooling or sheltering forest or a warming lake, river, or the sea.

Terroir is, in other words, the particular flavor that comes from a specific place with specific local conditions. While generally used to refer to wine, it has obvious applications for most foods and drinks.

Consider the way in which Scottish distiller Laphroaig markets its whiskies. Located on Islay in the Scottish Hebrides, they center their brand on the terroir of that cloudy, windswept island. For instance, their website describes the Càirdeas 2022’s “flavours of peat, smoke and sea salt that soar with bitter maritime character… elevated by a coastal character that can only come from sea spray and storms.” Laphroaig ages this whisky in a warehouse right on the island’s coast so that “exposure to rugged conditions tease out our enigmatic flavours and lend a maritime quality to the final whisky.” A decade ago, they advertised their single malt Scotch as “challenging by nature” — a complex, acquired taste that reflects the wind and weather of Islay.

Similarly, Steven Jenkins’ Cheese Primer, a guide to international cheeses, abounds in terroir statements. For instance, he attributes the blueness of stilton to the iron-rich soil in which the cows’ feed grows. He writes that the flavor of Loire Valley chèvre comes from the goats’ diet of local plants: “because of this lush pasturage, the goats’ milk is exceptionally rich and the cheese it produces is especially delicious, incorporating subtle nuances of clover, herbs, pine, walnuts and pepper.” When discussing French mountain cheeses like Beaufort and Tomme de Savoie, he argues that “it is necessary to identify certain valleys and mountains so as to differentiate between specific pasturages and thus pinpoint the best cheeses.”

Indeed, many of the world’s most famous cheeses still carry the names of the village or town in which they originated: stilton, cheddar, gouda, edam, camembert, Gruyère, Monterey Jack. I once read of a Chinese tea connoisseur so discerning that he could drink one cup and the immediately identify the specific mountain where the tree leaves had been grown. While this is probably an exaggerated if not wholly apocryphal story, it does reflect the importance of location, location, location in cuisine as well as real estate.

What does this mean for travelers looking to discover somewhere new after the claustrophobia of the COVID era? First and foremost, one should seek out each destination’s local specialties and appreciate them in their original context. The verb “pinpoint,” as used by Jenkins, is apt here — the traveler should identify these foods and drinks, and while there, appreciate how they makes use of the locally available plants and animals, the extent to which they are in most cases literally rooted in that area’s soil. In sum, the traveler should try to experience the food and drink of that “particular piece of earth” which he or she visits.

Terroir and Tradition

A cuisine is not simply the product of local people using local ingredients. As Mort Rosenblum notes in A Goose in Toulouse, even the most traditionalist of French chefs uses an originally Indian spice called black pepper. London restaurants have served curries for over two hundred years; Indian cuisine has become an integral, authentic part of English cuisine.

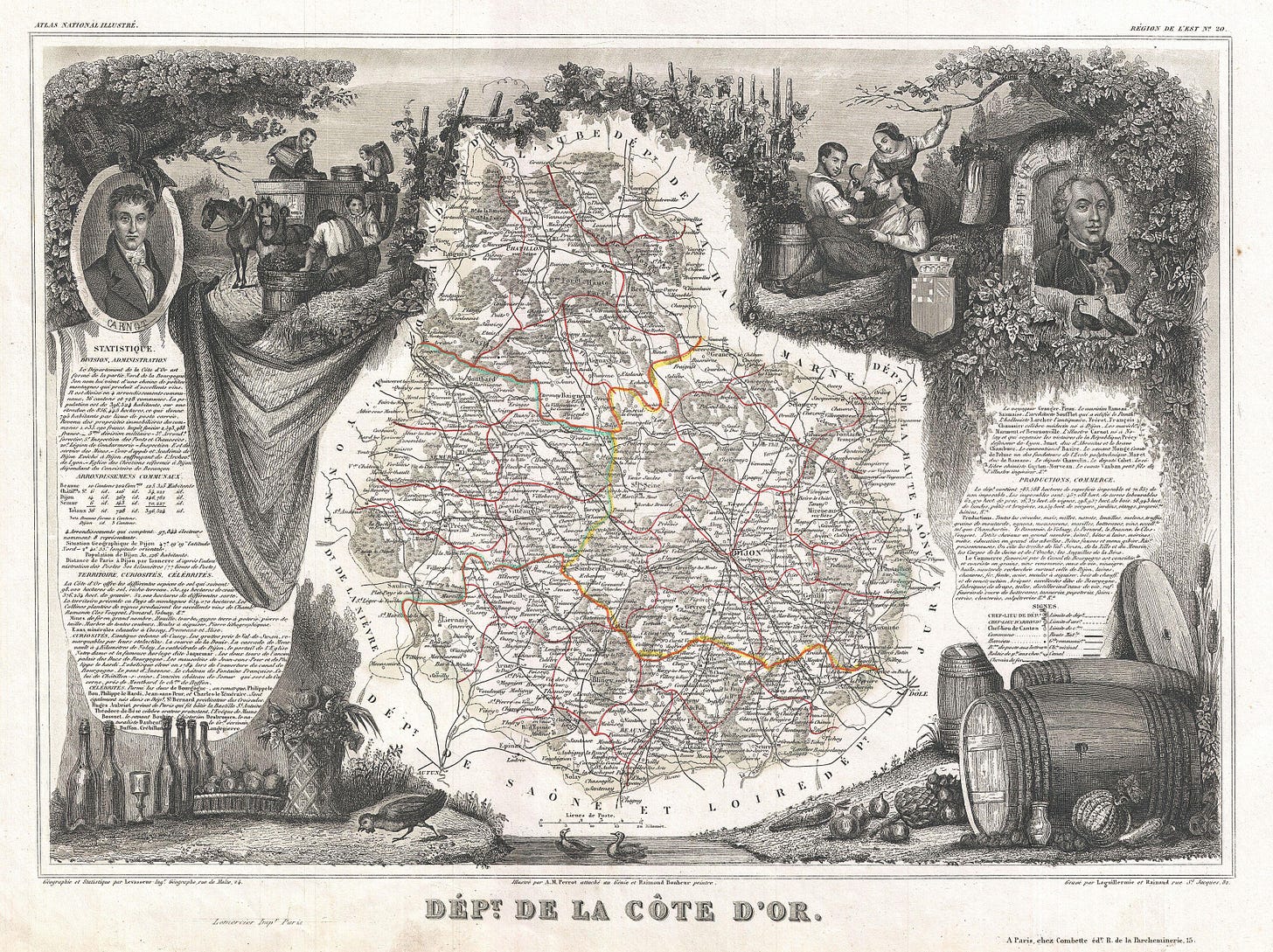

Thus the hungry or thirsty traveler should expand their definition of terroir to encompass the cultural landscape as well as the national landscape. To take an obvious example, there is no necessary connection between sparkling wine and the terroir around Reims and Troyes. Indeed, every French wine region makes its own sparkling wine, to say nothing of prosecco, cava and California champagnes. We call sparkling wine ‘Champagne’ because the traditional method of sparkling wine production originated in the Champagne region.

Champagne is France’s most famous appellation d'origine contrôlée, which means that only sparkling wine made in that region according to traditional methods can bear that name. Many other products have appellations, including more than 300 wines and dozens of cheeses. Beyond France, the European Union and United Kingdom’s Protected Designation of Origin or PDO covers dozens and dozens of regional products, including traditional Greek feta, prosciutto di Parma, Ardenne butter and Cornish clotted cream. While the PDO system is, like everything else in the world, dominated by business interests and political considerations, it is a good starting point for the traveler looking for something generally unavailable at home.

One obvious example come to mind. I’ve found that one of the great, underappreciated pleasures of traveling is visiting the local grocery store: seeing familiar brands in new packaging, or unfamiliar brand names, or, above all, selections of local wines, cheeses or other specialties, such as refrigerated rows of AOC cheeses in a French grocery store, each evoking a different corner of the country.

AOC and PDO are not the only guides to authentic local food and drink. My British readers are very familiar with the Cask Marque signs indicating that that particular pub has real cask ale. On the same subject, the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) gives out various awards to pubs and catalogues historic pub interiors. Again, politicking, corporate-bureaucratic inertia and simple human cliquishness undoubtedly play a role here, but these tools are certainly useful in the right situations.

As for myself, I have rather peasant tastes in cuisine while traveling. Instead of Michelin stars I prefer to the traditional alcoholic beverages, the traditional cheeses, the local dishes passed down from generation to generation, such as Alsace’s choucroute garnie, which I will use to illustrate how doing a bit of ‘homework’ can enhance the experience of dining in a new city.

A Reading of Choucroute garnie

The most salient fact about the Alsatian specialty choucroute garnie is that it has a French name despite consisting of the two most stereotypically German ingredients, sausage and sauerkraut.

This reflects what is probably the most salient fact about Alsace. Currently a region of France — part of the Grand Est administrative region — on the German border, it has more than two millennia of history as a meeting place and battleground, most famously between French and German-speaking peoples. Indeed, the name of its largest city, Strasbourg, comes from cognates of the modern German Straße, ‘street’, and Burg, ‘castle,’ which means something more like ‘fortified settlement’ or ‘city’ in placenames such as Hamburg, Augsburg, Ravensburg and Regensburg. (Variations of the same root appear in the name of U.K. cities such as Edinburg, Peterborough and Canterbury, and in American cities such as Pittsburgh, Greensboro and Gettysburg.)

Thus Strasbourg is literally ‘street-city,’ a crossroads. Many powers have conquered or otherwise controlled it, and Alsace as a whole, since Julius Caesar’s conquest in 58 BC: the Roman Empire, Frankish Kingdom, Carolingian Empire, Holy Roman Empire, French Ancien Régime, French Republic/Empire, German Empire, Nazi Germany, modern France. Between 1870 and 1945, Alsace changed hands from France to Germany to France to Germany to France, with many of its villages experiencing even more reversals during the two world wars. Old Hollywood director William Wyler (Ben-Hur, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, The Letter, etc.) was born in Alsace in 1902 and once told an interviewer about the confusion of growing up in contested territory during World War I. Every morning, he recalled, he would get up and ask his parents if they were part of France or Germany that day.

(My French readers may know the Alphonse Daudet story “La Dernière Classe,” about an Alsatian schoolteacher forced to switch from teaching French to teaching English in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War.)

These repeated collisions between France and Germany left more marks than sausage and sauerkraut. A visitor to Alsace will likely eat choucroute garnie along with a French wine with a German name, such as Riesling or Gewürztraminer. On the map, a handful of French names (Marmoutier, Florimont, Ribeauvillé) appear like islands in a sea of German towns and villages (Schiltigheim, Haguenau, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, Obernai and dozens more). The old, picturesque restaurant on Strasbourg’s cathedral square that every tourist photographs is called the Maison Kammerzell, its sonorous mix of French and German sounds shared with the names of many famous Alsatians: football manager Arsène Wenger, businessman Emile Henry Marcel Schlumberger, Napoleonic generals Jean-Baptiste Kléber and François-Étienne-Christophe Kellermann.

The most famous mixed French-German name comes from a much earlier conflict. Strictly speaking, Jeanne d’Arc came not from Alsace but from the neighboring region of Lorraine. These two regions, however, have such close historic ties that they were once a single administrative entity, Alsace-Lorraine, a joint name still used in in travel guides about the region. Jeanne grew up in a small town on the outskirts on the French-speaking world whose residents spoke a German-influenced dialect. (Domrémy is about as far from Strasbourg — then a free imperial city of the German-speaking Holy Roman Empire — as Los Angeles is from San Diego.) According to the surviving documents, she signed her name not as Jeanne but as Jehanne, a seeming hybrid between the French Jeanne and the German Johanna.

Choucroute garnie, an echt deutsch dish with a French name, is in other words not just a factoid, a little bit of trivia to be placed in a tourist brochure. In its own way it speaks to centuries of history.

Its two main ingredients take us back to a time before a French or German language. Why sausage? Because refrigeration is a quite modern invention and for most of history people had to find other ways of preserving food. Sausage-making, which involved salting, drying and/or smoking to preserve meat, is at least old enough to be mentioned by Homer, who does so in books 18 and 20 of The Odyssey. In the latter case, he compares Odysseus’s impatience to slay the suitors with that of a hungry person waiting for a sausage to finish roasting. The need to preserve meat led to the invention or adaption of sausage in many different cuisines: merguez in Algeria and Morocco, chorizo in Spain, lap cheong in southern China, an almost inexhaustible sausagefest in Germany.

The sauerkraut also reflects the ancient use of salt as a preservative. Like sausage, salted, fermented cabbage appears in many different cuisines, most famously as Korean kimchi. Choucroute garnie is generally served with boiled potatoes, which add another layer of history. Potatoes of course originated in the Andes Mountains and were the staple carbohydrate of the Inca Empire. Spread across the world by the Spanish Empire, the potato became as crucial to many European cuisines as two other New World imports, tomatoes and chocolate. The dish’s usual herbs and spices add destinations to this world tour: the Mediterranean (bay leaves), India (black pepper), Indonesia (cloves).

One could go on, for instance, by tracing the specific types of sausages used in choucroute garnie back to their origins in French and German towns, or by tracing any distant influence from ancient Roman cuisine. But this is just one specific example and I want to make a general point: the possibility of enjoying any traditional local food both in itself and in the way that it reflects histories of trade, war, technology and migration. It can be both food and food for thought.

Terroir and Books

Monterey, California has terroir in the culinary sense of the word. Well over a century ago, Scottish immigrant David Jacks began commercial production of a Spanish-influenced cheese made by local Franciscan friars. It became known as Monterey Jack and remains probably America’s most popular and most successful original cheese style. Anyone who knows Monterey Jack as a rather bland white supermarket cheese has a delicious surprise in store — the much more flavorful, authentic real Monterey Jack, as found in or near its original terroir.

Most visitors to Monterey, however, are not cheese connoisseurs. If they’re not in town to see the Monterey Bay Aquarium, they’re probably there to visit John Steinbeck Country. That aquarium is located on Monterey’s Cannery Row, a neighborhood known around the world via Steinbeck’s novel of the same name. In Monterey one can see locations from other Steinbeck novels, including Tortilla Flat and Sweet Thursday; one can shop, drink a cup of coffee or simply admire the oceanfront view at Steinbeck Plaza.

About half an hour inland is Steinbeck’s hometown of Salinas, where he would later set much of his fiction, including East of Eden. “I remember my childhood names for grasses and secret flowers,” he writes in the first chapter of that novel, which he wrote in part to share the Salinas of his childhood with his two sons. “I remember,” he continues in the next paragraph,

that the Gabilan Mountains to the east of the valley were light gay mountains full of sun and loveliness and a kind of invitation, so that you wanted to climb into their warm foothills almost as you want to climb into the lap of a beloved mother.

The fact that ‘Steinbeck Country’ is an established term, used in newspaper headlines, book titles and by San Jose State University’s Center for Steinbeck Studies speaks to my final point in this essay — the opportunity of expanding terroir from cuisine to literature.

Consider the British Isles. If you google the phrase “Jane Austen England,” for example, you will receive more than 33,000 hits, with the top results including articles titled “Take a Tour of Jane Austen’s England,” “9 Jane Austen Sites in London,” “A Guide to Jane Austen’s English Countryside” and “Take a Stroll Through Jane Austen’s England with this Interactive Map.” In Dorset, one can book cottages in or take walking tours of Thomas Hardy Country, which the author famously fictionalized as ‘Wessex’ in his novels and short stories. “Wordsworth Country” has more than 12,000 hits on Google; “Dickensian London” has more than 29,000; “Shakespeare Country” has more than 94,000.

I will myself visit Dublin later this year due in large part to 2022 representing the centennial of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a book I’d like to read in its terroir. I’m doing so because many of the best reading experiences of my life have involved a similar resonance between book and place. In a previous post I described the joys of reading Karen Blixen’s Winter’s Tales in wintry Denmark, the synchronistic way in which the tales and the landscape outside mutually amplified each other. In China I recall the joy of reading Lin Yutang’s art history translations and then looking out the window at the same kinds of distant, mist-shrouded mountains that haunted centuries of Chinese painters.

I had a similar experience in Steinbeck Country itself. A few years ago, I spent a few days in Monterey alongside two books by Steinbeck: The Pastures of Heaven, a collection of short stories set in the nearby Corral de Tierra Valley, and The Log from the Sea of Cortez, a nonfiction account of a scientific expedition across the Gulf of California with marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who inspired the character of Doc in Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday. While The Pastures of Heaven is well worth reading, very much the young Steinbeck’s attempt at writing his own Californian Winesburg, Ohio, Monterey and The Log from the Sea of Cortez combined to become a perfect pairing, a perfect example of literary terroir.

I could take a short walk past the aquarium to Ed Ricketts’ lab, Pacific Biological Laboratories, still standing at 800 Cannery Row. The aquarium itself of course had and still has specimens of the kinds of sea creatures studied by Ricketts.

The Log from the Sea of Cortez itself, not being one of the Steinbeck books assigned to high school students, has become overshadowed by his fiction. (It is the 18th most popular of Steinbeck’s book on Goodreads, with only 5,345 ratings compared to more than 480,000 for East of Eden, 835,000 for The Grapes of Wrath and well over 2 million for Of Mice and Men.)

As a result of remembered school curricula, among other things, we tend to remember John Steinbeck as, first and foremost, a socially conscious writer, a novelist if not the novelist of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. The Log from the Sea of Cortez, on the other hand, reflects another Steinbeck: the nature lover, the literary landscape artist, the capital-R American Romantic. (This Romanticism appears in its most concentrated form in Steinbeck’s overlooked third novel, To a God Unknown.) An unforgettable passage about the need to look back and forth between the tidepool and the stars — between the microcosm and cosmos — is in prose the kind of poem that a Californian Wordsworth would have written.

In between these moments of wonder The Log from the Sea of Cortez is a genial, sympatico book, an idyll, overflowing with curiosity, camaraderie and sheer joy in living. And, as someone prone to seasickness, I can’t think of a better place to read it than the beaches and clifftops of Monterey, looking up from the book at the port from which Steinbeck and Ricketts launched their expedition, or the blue waters they sailed through, or the horizon beyond, all the while smelling the salt spray and feeling the sea breeze.

To sum up, my best travel trip would be to seek out those culinary and literary resonances of that “particular piece of earth” upon which you find yourself. (These can, of course, be enjoyably combined; I’m certainly looking forward to reading a few stories from Dubliners over a pint of Guinness.) I’ve given only a few examples of how these resonances can increase enjoyment of and lead to new discoveries in a specific place, and vice versa.

Author’s Notes:

The William Wyler anecdote comes from the anthology Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood's Golden Age at the American Film Institute, edited by George Stevens, Jr.

Information on Jeanne (or Jehanne) d’Arc comes from Régine Pernoud’s J'ai nom Jeanne La Pucelle.

Robert, thanks for sharing this. I found it really interesting. Lots of great information and I enjoyed the information you had on Steinbeck.