On one level, I am not the right person to write a tribute to the Japanese manga artist Akira Toriyama, who died earlier this month. I have never read his most famous work, the manga series Dragon Ball, and know it only from its animated adaptation. I am completely unfamiliar with Toriyama’s other manga work, such as Dr. Slump, Sand Land, Jaco the Galactic Patrolman and the one-shots collected in Akira Toriyama’s Manga Theater. I have only dipped my toes into Dragon Quest, the long-running JRPG series featuring his character designs, and am a bit too young to remember the SNES classic Chrono Trigger, which also includes his artwork.

As for his overall cultural impact, I can only echo what you can read elsewhere. That Toriyama’s work in manga, anime and video games puts him alongside Shigeru Miyamoto, Hayao Miyazaki and Game Freak as one of the people most responsible for Japanese pop culture’s global popularity. That the diverse group of people who have paid tribute to him, from manga artists to video game designers to actors, musicians, athletes and professional wrestlers speaks to Dragon Ball’s ability to cross national, racial and cultural boundaries. That spontaneous and public overflow of powerful feelings, especially in Buenos Aires, speak to the emotional attachment many people have to Toriyama’s most famous work.

Nonetheless, I feel the need to write a few words about a world, a mythos that has given me a not insignificant amount of sheer joy, especially as a child in need of a fantastical world in which to escape. Because I am one of the millions of millennials from across the world who grew up with Dragon Ball/Dragon Ball Z and has not forgotten it.

Like The Lord of the Rings, Dragon Ball grew in the telling.

Beginning with a parody of the Chinese classic Journey to the West, Toriyama added influences from kung fu movies, The Terminator, American superheroes and space opera as he expanded his imaginary world manga chapter by manga chapter. “I don’t plan things out from the start,” he once told an interviewer. In the introduction to the first volume of the Dragon Ball manga, Toriyama writes that

The overall story is very simple, but I’d like to make up the finer details and the ending as I go along. That way, I can enjoy the suspense of wondering what I should do next, as well as the fact that I can draw anything I want to.

Goku, the central hero, combines aspects of at least four existing characters: the Monkey King Sun Wukong of Journey to the West fame, the Japanese folk hero Kintarō (a mountain-dwelling wild boy with superhuman strength), Superman (a supernaturally powerful, orphaned alien raised by a human family on earth in blissful ignorance of his real heritage) and the earnest, goofy, good-hearted Jackie Chan protagonist of films such as Drunken Master (1978).

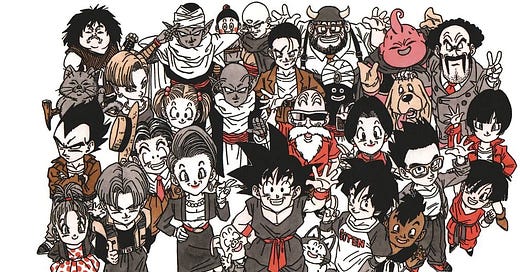

With an imagination that can only be described as mythopoeic, Toriyama incorporated all of these influences and more into his own colorful, fantastical, absurd, mysterious world of adventure. This world includes not just heroes and villains with incredible powers but also talking animals, the space-age vehicles and other technologies that Toriyama took such an evident joy in designing, literal gods, dinosaurs, portals to other dimensions, time travel, the afterlife and even such quotidian aspects of real life as driving tests and going to high school.

In doing so, Toriyama not only created the modern shōnen manga genre but also something like a mythology for millions of viewers. For myself and many of my contemporaries, aspects of this world remain as clearly remembered and as instantly available to the imagination as, say, lightsabers and Jedi knights or hobbits and ringwraiths: the possibility of becoming the legendary Super Saiyan, the healing Senzu beans, Capsule Corp’s capsules, Saiyans’ transformation into giant apes in the light of a full moon, the Spirit Bomb, the final forms of Frieza and Cell, King Kai’s small personal planet, the blue grass and green skies of Namek, the Hyperbolic Time Chamber.

Few who grew up with the anime could forget its vivid, larger-than-life characters: the Saiyan prince Vegeta, perpetually on the razor’s edge between healthy confidence and sheer arrogance; the lecherous old Master Roshi; the cyborg killing machine Android 18, whose original humanity is reawakened by Krillin’s kindness; the haughty, metamorphic, deliciously evil space tyrant Frieza, with no interest in redemption; Goku’s wife Chi-Chi, who becomes the consummate tiger mother; Goku himself, who never loses his good heart or his boyish love of eating, sleeping and exercise after all his growth and all his adventures.

I became a serious Dragon Ball Z fan in fifth grade. As a student in my first year at a new school, with a small social circle, I was in need of escape, of vicarious immersion into another world. The world I found via Cartoon Network’s Toonami block involved supernaturally powerful heroes and equally extraordinary villains flying through the sky, punching and kicking each other or shooting powerful energy blasts like the Kamehameha or Special Beam Cannon.

I was quickly enthralled by these characters and their saga, which I watched unfold in thirty-minute increments, once every weekday after school. It was something to look forward to at the end of the school day, at a time when I felt vulnerable in a way that only a child can feel vulnerable. And, just as importantly, it was a world awaiting discovery with the tireless enthusiasm only available in childhood.

I returned to Dragon Ball Z more than once, at times when I felt similarly adrift. During my last two years of high school, I dealt with serious insomnia and one of the few joys of those sleepless nights was discovering the very first season of the original Dragon Ball — Goku and Bulma’s initial quest for the dragon balls — available online. As before, I immersed myself in their adventure, which took my mind off of other things.

Almost a decade later, while studying abroad, I had a similar although thankfully briefer bout of insomnia. One late night or early morning I followed the YouTube rabbit hole down to a fan edit of the Saiyan Saga, which cut down dozens of episodes into one three hour-long movielike experience. I of course stayed up all night to watch it.

Looking back, I can identify three main reasons why the series both initially hooked me and has stuck with me. Three reasons, that is, apart from sheer nostalgia, which I recognize as a major pull in my life.

The first thing is the hardest to put into words. While Dragon Ball Z has its grim moments and its deaths on the battlefield, its overall flavor is that of optimism, of joy, of discovery and, perhaps above all, of free and effortless movement through space, of flight. People can fly in this world.

Toriyama’s inability or unwillingness to plan things out in advance, which created plotholes, retcons and other inconsistencies, also gave Dragon Ball Z an exuberant spontaneity, a child’s playfulness, a sprezzatura. If you Google “Akira Toriyama,” you’ll see him smiling in almost every picture; he clearly put this part of himself into his most famous creation.

Second, my world was very small as a fifth grader, comprising my house, elementary school and local neighborhood, with only very occasional excursions outside of this little circle. Like most children, I had a great hunger for adventure that I could only satiate through fiction, and Dragon Ball Z took its place alongside Star Wars and Narnia as one of the most satisfying meals in this regard.

As a child watching the series for the first time, I had even less of an idea where the story was going than Toriyama apparently did, which made the sense of suspense and of vicarious discovery that much more powerful. And of course Toriyama created such imaginative and unpredictable world for me to discover, one that combines fantasy’s vast wilds — the perfect canvas for adventure — with science fiction’s gadgets, vehicles, aliens and space travel.

Finally, Dragon Ball Z has long held a particular appeal for athletes due to its themes of self-improvement through training and discipline. In his words, Philadelphia 76ers forward Tobias Harris grew up with Goku as a role model because “he was always pushing to take that next step to become a Super Saiyan… There are so many life lessons on the show about unlocking your own potential.” Dragon Ball Z is an epic of perseverance, applicable to people in all walks of life.

This focus on personal growth is also present at a more global level; the constant training to reach the next physical level is only the most obvious example. Unlike, say, the Pokémon anime, which tends to feature a return to the status quo ante at the beginning of every season, Dragon Ball Z follows its characters forward through time, through relationships, childbirth, parenthood, aging, and even death.

The series begins with the young, monkey-tailed wild boy Goku meeting the impetuous teenaged Capsule Corp. heiress Bulma. It ends with Goku as a husband, father and mentor and Bulma as a middle-aged wife, mother, inventor and businesswoman. While many characters are killed in battle and then return to life through supernatural means, some — most notably Goku’s adoptive human grandfather — remain dead. Three of the strongest heroes, Piccolo, Vegeta and Android 18, began as villains before undergoing a change of heart.

This theme brings us to the titular dragon balls themselves. When brought together, these seven orange-gold balls summon immortal dragons who can make wishes come true. But they are dispersed across the entire world and can only be reunited after a long journey.

As an adult in my thirties, this strikes as the perfect, imaginative, fantastical metaphor for an essential aspect of life; embarking on a true journey, whether external, internal, or both, is the only way to make a wish come true in our world as well.

Thank you, Akira Toriyama, and may your heroes live long, grow, train hard, face their fears and pursue the seven dragon balls to the ends of the earth and beyond it.

Love it. I still mourn and sad about this. His works really influenced me as a kid growing up to be an artist. May you rest in peace, Sensei. Thank you for your wonderful works.

This is the *third* such tribute I've read to Toriyama across all the 'stacks I follow, and I couldn't otherwise imagine a common interest between yours and theirs - just goes to show how deep DBZ's appeal runs across so many demographics.