Altmanesque I

introduction and the sixties

It feels homegrown and handmade. There have been a hundred who have tried to be Robert Altman – or Altmanesque – but they miss that certain ingredient; they aren’t him. There’s no one like him. He can be imitated and he can influence, but he’s impossible to catch up with or cage – he’s unpredictable, and the river he follows is his own.

Paul Thomas Anderson, foreword to Altman on Altman

In my tribute to the late, great David Lynch earlier this year, I noted that cinephiles’ use of the adjective Lynchian speaks to the uniqueness of his creative vision and to his influence on other filmmakers.

Robert Altman, who was born about a century ago, is another member of that small club of directors whose names have become adjectives.1 The Oxford English Dictionary defines Altmanesque as “of or relating to the film director Robert Altman; resembling or characteristic of his films or his style” and notes that “Altman's films typically feature several overlapping storylines and multiple protagonists, presented in a naturalistic, improvisational style.” The word2 appears in headlines from The New York Times, The Guardian, the Chicago Reader, Deadline and The Irish Times, in the titles of academic papers and in countless film reviews.

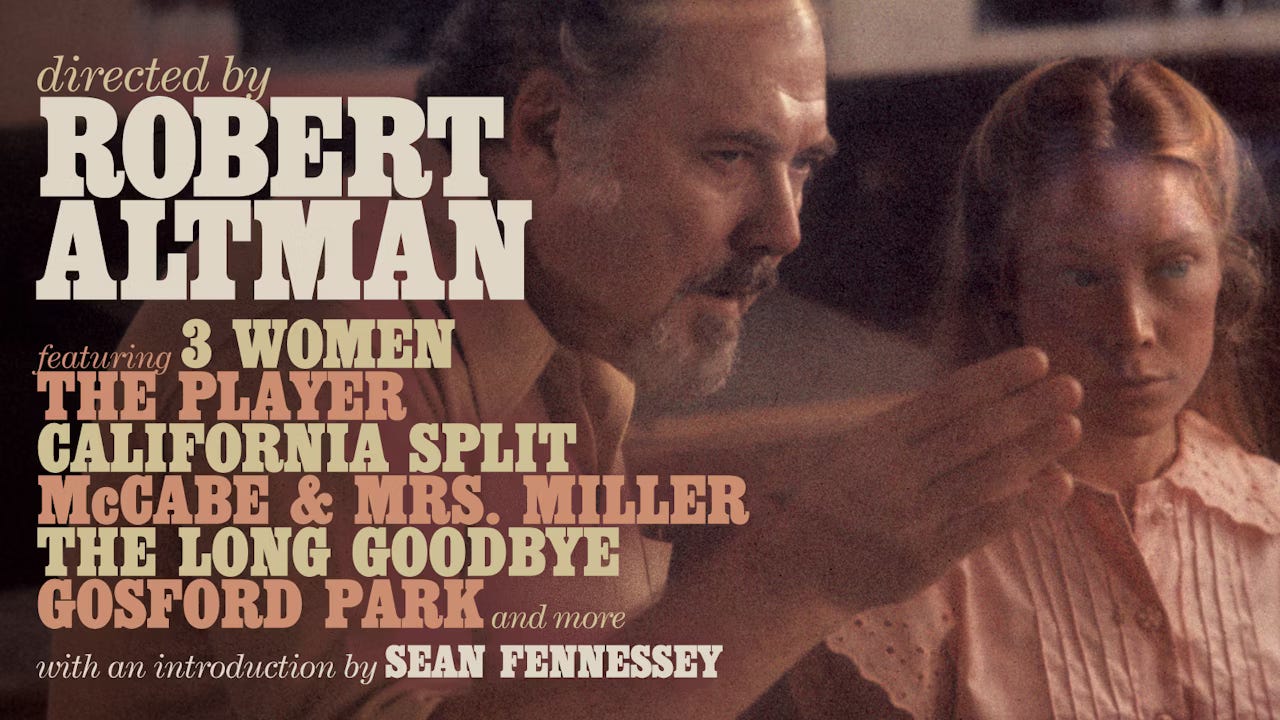

The Criterion Channel, which itself describes Magnolia (1999) as “Paul Thomas Anderson’s Altmanesque portrait of a day in the crisscrossing lives of various San Fernando Valley residents,” is currently celebrating Altman’s centennial with a retrospective of more than twenty of his films. A perfect opportunity for a deep dive into one of the classic American filmographies, which I’m going to do in a series of Substack posts. In addition to watching the films themselves, I’m currently reading Altman on Altman, a book-length interview between Altman and British film critic David Thompson.3

My plan is to divide this deep dive into three posts: this post, introducing Altman and covering his first feature films; a post on Altman’s seventies films; and a post on his later films/a consideration of his overall legacy as a filmmaker. This is of course subject to change and subject to the spontaneous moments of creativity that Altman himself prized. I invite you to join me on this little journey through film history.

I’ve never studied Robert Altman. In fact, I did not watch a single Robert Altman movie in film classic, either in community college or university. One obvious reason for this is that film history – which spans just over 130 years as of 2025 – is simply too vast to be explored in any class or even any degree program. There just isn’t enough time to cover every classic film or every major filmmaker.

In the case of Altman, an equally important factor is the difficulty of fitting him into curricula because he does not fit comfortably into any genre or movement or era.

On some level, Altman can and should be thought of as one of the key New Hollywood filmmakers. After directing his first film in 1967, the year generally identified as the starting point of the New Hollywood era, Altman became one of the first major post-Cassavetes filmmakers to focus on improvisation, employing a spontaneous, collaborative, informal approach to filmmaking that made him American cinema’s equivalent of jam bands like The Grateful Dead.

Altman’s insistence on naturalistic, overlapping dialogue — with characters speaking at the same time, interrupting each other, and finishing each other’s sentences — both got him fired from his first feature film and led to subsequent films’ pioneering use of multitrack dialogue recording. From M*A*S*H (1970) to Nashville (1975), whose soundscapes incorporate 24 different audio tracks, Altman and his collaborators pushed cinematic sound design to the absolute technological limit.

On a broader thematic level, Altman’s seventies films resonate with the decade’s zeitgeist in their subversive, ironic takes on icons of American history and culture. From the military to the old west, the noir detective, country music and Hollywood itself, Altman and his collaborators did more than their share of knocking off pedestals, replacing clear conflicts between hero and villain with complex webs of relationships between flawed characters.

Altman, in short, was one of the major filmmakers of the New Hollywood era, however we define that era’s beginning and endpoint.4 On the other hand, he had a very different background than his New Hollywood peers. He was not a critic-turned-filmmaker, like Peter Bogdanovich or Paul Schraeder, or a film school graduate like George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola or Martin Scorsese. He did not graduate from the Roger Corman school of filmmaking5 like Bogdanovich, Coppola, Scorsese, Robert Towne or Dennis Hopper.

Instead, Altman’s path to Hollywood success wound through unsuccessful attempts at breaking into Old Hollywood as a screenwriter, making educational and industrial films in Kansas City; and directing episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Bonanza and other late fifties and sixties television shows. Altman was a generation older than many of his peers, already an adult World War II veteran before New Hollywood luminaries like Schraeder and Steven Spielberg were born and already 45 by the time he became a name director with M*A*S*H in 1970.6

Altman, in other words, is one of the great late bloomers in film history, someone who spent years working before finally emerging as an artist relatively late in life. After a bumpy 1980s, which saw a return to television Altman had a career renaissance in his late sixties and seventies, earning Best Director nods for The Player (1992), Short Cuts (1993) and Gosford Park (2001) and directing his last movie at age 80. In addition to predating New Hollywood, then, Altman also outlasted it by finding critical and commercial success in the very different cinematic landscape of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Altman in the Sixties

Countdown (1967)

Based on the novel The Pilgrim Project (1964) by Hank Searls, Robert Altman’s mainstream feature film debut7 stars James Caan and Robert Duvall in a pre-Apollo 11 story of the first American moon landing. Warner Brothers fired Altman late in production over his use of overlapping dialogue; per Altman’s telling, Jack Warner himself objected to it. After Altman’s firing, the studio rewrote his original ending, and, in his words, “cut the picture for kids.”

Nonetheless, the finished product has a few embryonic auteur signatures, if you’re looking for them. For one, Countdown presents a more grounded depiction of space exploration than many sixties science fiction films. Literally grounded, as its spaceflight and moon landing sequences are the finale of a story that unfolds on earth, in NASA conference rooms, training facilities and astronauts’ homes.

In Altman’s own words, “I tried to show astronauts as human beings with problems.” James Caan’s astronaut protagonist is not an unflappable hero but someone struggling in a high-pressure situation and worried about the moon mission’s potential dangers. NASA puts him in that potentially dangerous situation for political reasons: as a reaction to the surprise announcement of a USSR space mission that will beat the planned Apollo Program to the moon. Apollo is put on hold in favor of Project Pilgrim, a rushed one-man moon mission that might be able to beat the Russians in this lap of the Space Race.

This decision causes internal conflict at NASA. Robert Duvall plays the astronaut who would have commanded that canceled Apollo mission. Assigned to train his own replacement, he takes his jealousy out on Caan’s astronaut by pushing him to his limit during the accelerated training process.

If the next year’s 2001: Space Odyssey represents cinema’s great mythicizing epic poem of space exploration, then Countdown offers something much smaller and more prosaic. It’s not a great film, or even a particularly good one, but it is a piece of film history, not just for Altman but for its two lead actors who each went on to long, successful Hollywood careers. And, despite the studio’s negative reaction, the final cut does feature one three-way discussion/argument with characters talking over each other. One small prototype for future Altmanesque dialogue.

That Cold Day in the Park (1969)

“It was really a first film in a funny way,” Altman would later tell David Thompson. “Very pretentious and stylized.” Much of this stylization comes from cinematographer László Kovács, who pulls mirror shots, shots through windows, shots through distorting glass, handheld camera shots, bokeh and other showy techniques out of his bag of tricks.8

Based on the novel of the same name by Richard Miles, That Cold Day in the Park was adapted by Gillian Freeman and shot on location in Vancouver. After failing to get superstars Elizabeth Taylor or Ingrid Bergman for the leading role, Altman’s team cast Oscar-winning actress Sandy Dennis as the protagonist.

It was produced and distributed by the short-lived Commonwealth United Entertainment and funded by Altman’s friend/Max Factor heir Don Factor, and premiered at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival. A young Roger Ebert gave it 1.5/4 stars, comparing it unfavorably to Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and writing that “the plot is too improbable to be taken seriously.”

Ebert goes on to observe that the film “doesn’t declare itself as a horror film until too late,” which is an astute observation. That Cold Day in the Park has an intriguing inciting incident – a sheltered young lady sees a mysterious, nameless mute young man sitting by himself on a park bench in the rain and invites him to take shelter in her house – that doesn’t really go anywhere until the twisted psychosexual horror of its last twenty minutes.

Looking at the film in the context of Altman’s career, it’s notable for two reasons. First, it represents the beginning of Altman’s relationship with key creative collaborator Leon Ericksen, who would design the wings in Brewster McCloud (1970) and work as an art director or production designer on McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), Images (1972), California Split (1974) and Quintet (1979).9 Second, it seems in hindsight like a dry run for Images and 3 Women (1977), future Altman movies with surreal, dreamlike, sinister atmospheres.

“After I was hired on M*A*S*H,” Altman recalls in Altman on Altman, “Dick Zanuck saw That Cold Day in the Park and said, ‘If I’d seen that picture before, I’d never have let that guy get near!’” But Zanuck did not see the film until it was too late and Altman finally got his big break. My next post will begin with that story.

3 Women (1977), a dreamlike film written, produced and directed by Altman (and inspired by a dream he had) is the rare film that can be described as both Lynchian and Altmanesque.

Or the variation Altman-esque.

If you’re not familiar with the ____ on ____ series of filmmaker interview books, I’d highly recommend them. I’ve read Scorsese on Scorsese, Burton on Burton and a few others.

The received narrative is that the success of Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) combined with the debacle of Heaven’s Gate (1980) marks the death of New Hollywood c.1980. I think that’s an oversimplification, but that’s a topic for another post.

In his introduction to the Criterion retrospective, The Big Picture podcast host Sean Fennessey groups Altman with Sam Peckinpah and John Frankenheimer, two other New Hollywood-adjacent filmmakers whose careers as television directors predates what we’d generally consider the New Hollywood era. I think there’s a strong case for conceptualizing Altman, Peckinpah, Frankenheimer, Sidney Lumet, Arthur Penn, Franklin J. Schaffner and a few other names as a “middle generation” of filmmakers between Old and New Hollywood, directors who started in fifties television and worked on both sides of the Old/New Hollywood divide.

In between his work on industrial films in Kansas City, Altman directed a low-budget teen exploitation movie called The Delinquents (1957). It is not included in Criterion’s retrospective.

Alongside his friend and colleague Vilmos Zsigmond, Kovács (1933-2007) immigrated to the United States after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and became one of the key New Hollywood cinematographers. His filmography includes Targets, Five Easy Pieces, Paper Moon, The Last Waltz and Ghostbusters.

Ericksen’s biggest impact on pop culture is probably his work as the second unit art director on Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977). Among other things, he designed the bantha costume worn by an elephant named Mardji.

Haven’t seen these two but I will for sure check them out. Sounds straight up my alley especially relating to my own filmmaking journey. The late bloomers always give me hope!

What are you thoughts on what seems like an almost post-modern approach to film genres (e.g., the war film, westerns, detective noir, etc.)--post-modern in the sense that the genres are part of the content. And what do you make of his attitude towards these genres? Off the top of my head, I want to say his attitude is derisive--maybe mocking and bitter towards Hollywood, with *The Player* being the ultimate expression of this? I haven't seen these films in a long time, so I could be really off base.

(On a related note, do you think that Altman influenced the Coen Brothers with regard to this treatment of Hollywood genre movies? I feel like they also wanted to tinker and update these genres, but they seemed to have a more positive, loving view of them.)