On my other Substack, I’ve recently posted about the Pokémon Charmander, a creature descended from the mythological salamander as opposed to the zoological salamander. Both creatures seemed to have existed simultaneously in medieval Europe: the slimy little amphibian, which inhabited forests and wetlands, and the creature with a miraculous invulnerability to fire, which took multiple forms and inhabited the pages of the bestiary.

This theme will run throughout the Necessary Monsters series. While some Pokémon, such as Krabby or Kingler, seem like direct translations of real animals, others reflect animals that have already been transformed into legendary creatures. The Pokémon Vulpix and Ninetales, for instance, take from the mythicized fox known as the kitsune rather than the real animal. Clefairy and Clefable take influence not from the real rabbit but from the legendary moon rabbit.

Because of this, I thought that a post on this topic would be worth writing, not least because it would appeal to both Necessary Monsters and Earthly Delights readers.

How can animals live simultaneous lives as symbols and as real species? How can the former (as in the case of the salamander) become so disconnected from the latter as to basically share just a name?

Before directly answering this question, it might be worth considering a parallel from human history: pirates.

On one hand, piracy is a historical reality. It has occurred at many times and in many places, including the contemporary Indian Ocean and Gulf of Guinea. Famous pirates like Bartholomew Roberts and Captain William Kidd are real historical figures, with birthdates, birthplaces, causes of death and other associated facts.

On the other hand, the word pirate conjures up a series of phrases and images with mostly tenuous connections to historical pirates: “yo ho ho and a bottle of rum;” “shiver me timbers;” “dead men tell no tales;” parrots on shoulders; the Jolly Roger, walking the plank, x marking the spot on treasure maps; chests full of golden coins buried in the sands of desert islands. These images, of course, come from Treasure Island, swashbuckler movies and Disneyland’s Pirates of the Caribbean rather than any historical account.

This imagery has taken on a life of its own, free from any connection to historical piracy. During my childhood, for instance, pirate imagery was an inescapable cliché of game design; 2d and 3d platformers had their pirate level alongside the requisite ice level, desert level, grassland level and haunted house level. I opened treasure chests, climbed up palm trees and explored sunken ships as Super Mario, Banjo and Kazooie, and Donkey Kong. While doing so, I never connected these levels to piracy in the real world. For one, I knew almost nothing about any real pirates. More importantly, they seemed to stand alone without real-world context, as self-sufficient as a fantasy world populated by dragons and elves or a science fiction world with its spaceships and alien species.

The Pirate – as opposed to any individual historical pirate – has taken on a life of his own. Why? Because he speaks to some of our oldest wishes. He is an archetype of adventure, of freedom, of escape from everyday life.

If you live near the coast, or have ever visited a coastal town, the sight of a departing ship has likely sent you into a daydream about what it would be like to be on that ship, sailing away from your world and towards whatever’s over the horizon. If you’re anything like me, you might have briefly indulged in a reverie about the nautical life, about leaving home and sailing the high seas from port to port, never staying too long in one place.1

A ship, then, is already a powerful symbol. Combine it with a character defined by living outside of society and its rules and you have a powerful appeal to the romantic side of our imaginations. So powerful, in fact, that the pirate’s settings, props and other accoutrements have taken on lives of their own – so much so that they can communicate the pirate’s meaning even in his absence. A skull and crossbones flag or treasure chest alone is enough to suggest the whole scene, the whole series of associations, the whole atmosphere of freedom and adventure and discovery.

I propose thinking about mythicized animals as the result of a similar process, a similar drift away from reality assisted by the creativity of storytellers and visual artists. As with the pirate, this drift happens because the heraldic archetype of the animal – rather than any individual member of that species – makes a special appeal to our imaginations and/or reflect some aspect of our human experience.

Even though we live much farther from the world of animals than our ancestors, our own world of signs and symbols offers a glimpse of the animal kingdom’s symbolic power.

When we want to insult someone, for instance, we often compare them to an animal: to a rat, a pig, a sheep, a snake in the grass. We accuse them of being chicken, dogging it, crying crocodile tears, horsing around, aping someone else, fighting like cats and dogs. (And other, more vulgar comparisons.) An elephant in the room, a fly on the wall, a sitting duck, a dark horse, a bull in a China shop, a deer in the headlights, a fish out of water: a zoo’s worth of animals inhabit our cliches.

Consider the twenty national flags featuring animals, including the Albanian two-headed eagle, the Bhutanese dragon, the Guatemalan quetzal, the Mexican eagle and serpent and the Sri Lankan lion. Within the United States, consider the bear of California, the pelican of Louisiana, the elk, moose and eagle of Michigan, the bison of Wyoming. Corporate logos offer another menagerie: Penguin Books, Red Bull, Jaguar, Lacoste, MGM, Mozilla Firefox.

Despite living in a technological, industrialized world, one in which we spend significant resources on keeping our spaces free of animals, our language and visual culture abounds in animals. If we encounter a zoo of symbols in the internet age, imagine the richness of animal symbolism in an agricultural world, a world of daily coexistence with and observation of animals, their behavior and their life cycles.

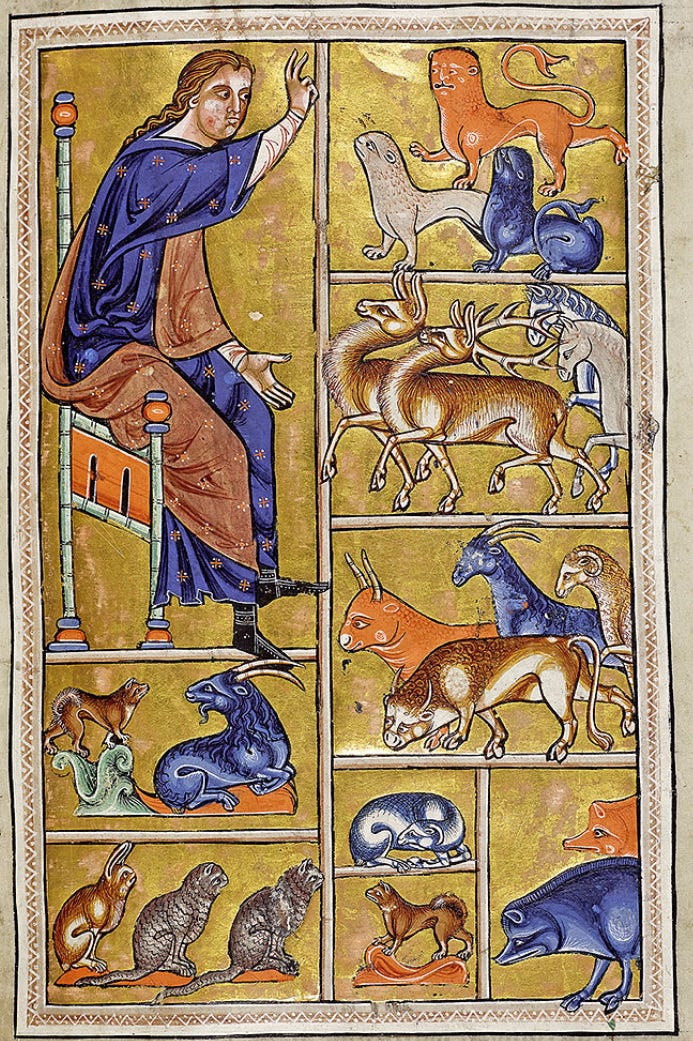

The medieval European bestiary offers possibly the best example of this. In the bestiary, real animals exist alongside dragons, unicorns, phoenixes and basilisks and take on something of these mythical creatures’ magical quality.

In a mostly illiterate society, the bestiaries’ main readership consisted of priests, who used bestiaries as sources of animal similes and metaphors for their sermons. In their own way, the bestiary animals each represent aspects of Christian life and belief:

Lions are born dead and remain that way for three days until their father breathes life into them in an echo of Christ resurrected after three days in the tomb.

Wolves reflect the devil, “darkly prowling around the sheepfolds of the faithful so that he may afflict and ruin their souls.”

Dogs represent priests, the watchdogs of the faith who guard their flocks.

Old eagles fly up to the sun and then descend into a fountain, where they are rejuvenated; this provides an example for the faithful, who should “seek for the spiritual fountain of the Lord” and life their eyes up to God.

Larger fish eating smaller fish provide “a parable for the instruction of men” – a warning about the world of endless predation created by the strong exerting power over the weak.

Of course, lions are not really born dead and eagles are not reborn in fountains, just as pirates didn’t actually bury treasure on desert islands or record these locations on treasure maps. The bestiarists concerned themselves not with scientific fact but with spiritual meanings, meanings mostly absent from animals in our 21st century imaginations.

To continue with the pirate analogy, this layer of added myth and legend – sometimes spiritual allegory, sometime whimsical storytelling – represents the animal kingdom’s equivalent of an archetypal swashbuckler. In both cases, imagination has transformed reality into something new. The bestiary animals lived new lives in the world of culture, just as movie and theme park pirates embarked on fictional adventures untethered to historical fact. In the bestiary texts and illustrations, in heraldry, in beast fables and in church art and architecture, animals became almost hieroglyphic representations of aspects of the human experience, hieroglyphics still used today in corporate logos, animated cartoons and other media.

This process was of course in no way specific to medieval Europe. The bestiary texts themselves, for instance, were often copied from classical Greco-Roman authors and thus reflect the animal mythologies of both that world and medieval Europe. In premodern and early modern Japan, the real fox coexisted with the bewitching, shapeshifting, nine-tailed kitsune; the real racoon dog coexisted with the jolly, mischievous, shapeshifting tanuki.

Yes, I’m writing about Pokémon because of millennial nostalgia, but also because Pokémon offers an echo, a glimpse of that intersection between zoology and mythology, of that transformation of reality into legend.

If you’re like me, this flight of fancy is soon grounded by prosaic considerations like seasickness, cramped spaces onboard, and personal responsibilities.

"Despite living in a technological, industrialized world, one in which we spend significant resources on keeping our spaces free of animals, our language and visual culture abounds in animals." Love this! It's so true!!!

> Even though we live much farther from the world of animals than our ancestors,

I'm not sure that's true for the animals in question. There were no lions in Europe during the medieval period. And most of the animals featured most predominantly in bestiaries might as well have been dragons and unicorns for how likely the bestiaries' readers were likely to encounter them.