There didn’t have to be lessons or a moral to the story; things could drift in and out and stories could ramble and be more effective in glimpsing moments of truth rather than going for the touchdown. They could be long, they could be musicals without people singing, and they could be dirty and smart at the same time. Beginning, middles and ends could all flow delicately together in any order, and weren’t even needed to be a great film. Things could just happen without explanation or too much fanfare, and the results would take care of themselves. This has been Bob’s great contribution: it doesn’t have to be spelled out.

Paul Thomas Anderson, foreword to Altman on Altman

Criterion Channel Robert Altman retrospective.

M*A*S*H (1970)

After failing to land a bigger name,1 producer Ingo Preminger – Otto’s brother – hired the relatively unknown Robert Altman to direct an adaptation of MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors (1968) by former combat surgeon Richard Hooker.2 Working from and taking liberties with a screenplay by Ring Lardner, Jr., Altman finally had the resources, collaborators and creative freedom to come into his own as a filmmaker. In his words,

It was a cheap picture that Fox thought would just play in drive-ins, and they didn’t care too much about it. Fox had two other war movies going on: Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora!, both big-budget pictures. I knew that and decided that the way to keep out of trouble was to stay out of their sightline – and the best way to do that was not to go over budget or over schedule.

Working under the radar, Altman, Preminger and their team assembled an incredible acting ensemble, including Donald Sutherland, Robert Duvall, Tom Skerrit, Gary Burghoff, former pro football player/future blaxploitation icon Fred Williamson and future Altman regulars Elliott Gould, Sally Kellermann and René Auberjonois. After firing one cinematographer over creative differences, Altman hired semi-retired Hollywood veteran Hal Stine, who was, in Altman’s words, “used to working fast” and willing to work towards the director’s unglamorous vision.

Its opening remains one of the most arresting in American history: Beach Boys-esque vocalists singing lyrics about suicide combined with aerial shots of helicopters transporting dead bodies.3 This sets a sardonic, unsentimental tone for the rest of M*A*S*H, which will break every rule for Hollywood war movies.

This is a war movie with zero onscreen combat but blood-splattered surgery scenes, a nominal Korean War period piece that’s really about Vietnam, and the very first mainstream Hollywood movie with an audible fuck. Instead of brave, self-sacrificing heroes, the men of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital are deeply flawed human beings under pressure, bored and horny, pursuing a variety of distractions: drinking; flirting; having sex; beefing with each other; dick measuring, both metaphorical and literal; stealing and recreationally using medication; voyeurism; spiteful pranks; watching movies; staging a mocking recreation of The Last Supper; playing football; betting on football; cheating on football. The climactic football game, with its cheerleaders and angry coaches, evokes the imagery of American high school to emphasize the character’s sheer adolescence, a theme picked up on by Pauline Kael and other critics.4

Some of the characters’ chauvinistic boys-will-be-boys behavior –especially the humiliation of Major Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Kellermann) – plays differently in 2025 than it did in 1970, but there is interpretive room to read the depiction of this behavior as part of the film’s broader anti-war, anti-establishment message, as a symptom of a general dehumanization and desensitization.5

A film that follows not one central hero but a fractious community; an episodic story eschewing traditional structure; a sound mix less concerned with clear lines of dialogue than an immersive, evocative soundscape; a subversive, sarcastic but not entirely unsympathetic approach to something quintessentially American: M*A*S*H represents the birth of the Altmanesque.

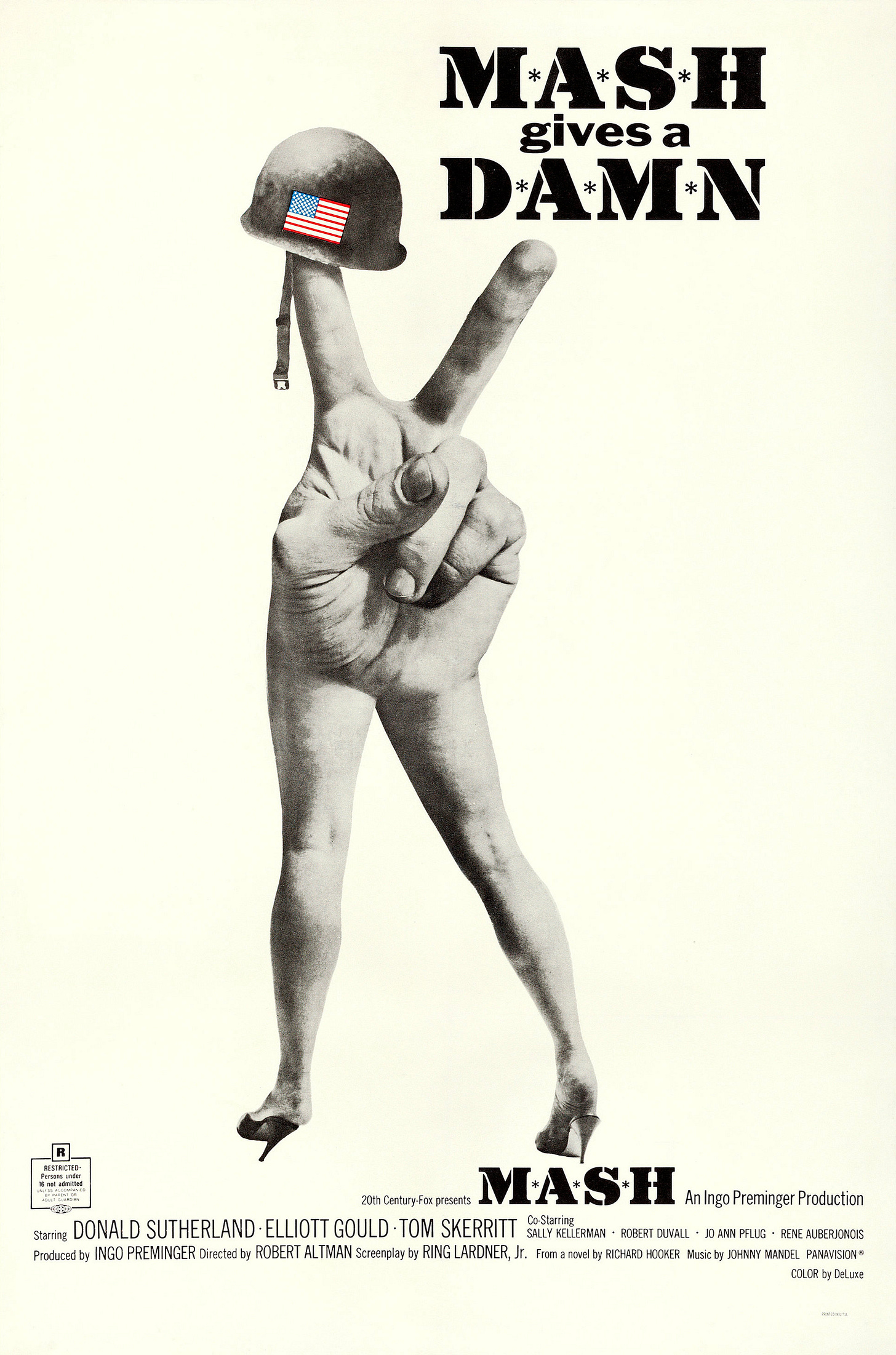

It was also the right film at the right time. Its classic poster, which combines the peace sign and middle finger, perfectly encapsulates a message that resonated with 1970 America’s antiwar/countercultural movement. It grossed more than $80 million on a $3 million budget, becoming the third highest-grossing film of 1970.6 Roger Ebert gave it 4/4 stars, writing that

One of the reasons M*A*S*H is so funny is that it's so desperate. It is set in a surgical hospital just behind the front lines in Korea, and it is drenched in blood. The surgeons work rapidly and with a gory detachment, sawing off legs and tying up arteries, and making their work possible by pretending they don't care.7

After winning the Grand Prix at Cannes, it received five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Supporting Actress for Kellermann. (Ring Lardner, Jr.’s adapted screenplay was its only win on a night dominated by Patton.)

And, of course, it spawned a massively popular tv show that ran from 1972 to 1983 and ended with a season finale that remains one of the most watched shows in American television history. Robert Altman was not involved with the show; he had a golden decade of feature filmmaking ahead of him.

Brewster McCloud (1970)

Quentin Tarantino, using a very Quentin Tarantino turn of phrase, describes Brewster McCloud as “the cinematic equivalent of a bird shitting on your head” in Cinema Speculation. Bird droppings are indeed a running motif throughout the film, beginning with the opening credits sequence, which ends with a bird shitting on a newspaper headline about Vice President Spiro Agnew. The poster shows the cast covered in bird droppings. One of the film’s main plot threads follows police investigating a serial killer who murders wealthy Houston residents and leaves their bodies covered in bird droppings.

The killer may or may not be the titular Brewster McCloud (Bud Cort, who had a small role in M*A*S*H), a young virgin loner who lives in a fallout shelter under the Houston Astrodome with his pet raven and dreams of flying away on his own homemade, Wright Brothers-inspired wings. Two women enter his life: his guardian angel (the previously mentioned Sally Kellermann, with the visible scars of amputated wings on her back) and Astrodome tour guide/lover interest Suzanne (Shelley Duvall in her film debut).

A loose retelling of the Icarus myth that’s also a police procedural and a quirky, awkward romantic comedy, Brewster McCloud features both a Bullit (1968)-inspired car chase and a metafictional, Felliniesque ending. It is a truly strange film.

As with M*A*S*H, this film’s opening sets a tone for the rest of the runtime. Altman regular René Auberjonois plays an ornithologist who addresses the audience directly from a study cluttered with bird skeletons and stuffed specimens. He begins to lecture on the topic of “man’s similarity to birds/birds’ similarity to man,” quoting Goethe on human dreams of flight. As he expounds upon the destruction of bird environments and the potential necessity of “enormous environmental enclosures to protect men and birds from each other,” the film cuts to an establishing shot and then pans to the Houston Astrodome, the gigantic birdcage that holds Brewster McCloud. Contra Paul Thomas Anderson, this is an Altman movie that spells it out, that begins by telling the viewer exactly what it’s about, thematically: flight as freedom, as escape from personal and social limitations.

Like the public address announcements in M*A*S*H, the ornithology lectures continue throughout the film and serve as segues between scenes. The running joke is the relevance of the descriptions of avian anatomy/behavior/mating rituals to the human action onscreen, as if American society and customs were the strange social structures of an exotic, newly discovered bird species.

Funded by Rock & Roll Hall of Fame producer/manager/executive Lou Adler, who had previously produced the classic rockumentary Monterey Pop (1968), Brewster McCloud was the first film made by Altman’s short-lived independent production company, Lion’s Gate Films.8 Altman and his collaborators completely rewrote the original screenplay by Doran William Cannon, the film’s credited writer. “He chose to ignore his SOURCE entirely,” Cannon writes in a bitter, self-pitying 1971 New York Times article.9

Brewster McCloud opened 11 months after M*A*S*H with a premiere at the Houston Astrodome on December 5th, 1970. It received mixed reviews and flopped, grossing $1.3 million on a budget of at least $1.8 million. “Most of the time,” Vincent Canby writes in his New York Times review, “the film is dim, pretentious, and more than a little cruel.”

Selling a whimsical, R-rated fable – part Icarus, part Peter Pan, part detective investigation, part social satire, part vintage 1970 countercultural weirdness – would be a hard ask for any marketing department. That same weirdness gave it a second life as a cult classic. (I wonder if it had any influence on 1985’s Brazil, a film that visualizes its protagonist’s dreams of donning artificial wings and flying away from his dystopian society.)

In the last post, I called Altman the cinematic equivalent of The Grateful Dead. Jerry Garcia famously compared the Dead and their cult following to licorice: “Not everybody likes licorice, but the people who like licorice really like licorice.” If Robert Altman’s filmography is a candy aisle, then Brewster McCloud is the black, salty licorice I’ve eaten in Denmark. People who like its very particular flavor of cinema might love it, while people who don’t might agree with Tarantino.

Per David Thompson in Altman on Altman, Stanley Kubrick, Sidney Lumet, Sydney Pollack and George Roy Hill were on Preminger’s wishlist of directors.

MASH stands for Mobile Army Surgical Hospital.

Robert Altman’s teenage son Mike wrote the lyrics to “Suicide is Painless.” Johnny Mandel wrote the music and arranged the song, which was performed by uncredited session singers and musicians.

In her words, “The profanity, which is an extension of adolescent humor, is central to the idea of the movie. The silliness of adolescents - compulsively making jokes, seeing the ridiculous in everything - is what makes sanity possible here.”

To quote Robert Altman himself, “I was accused of being a misogynist. They were asking how could I treat women in this way? I said, ‘I don’t treat women that way. I’m showing you the way I observed women were treated, and still are treated, in the army.’”

The year’s biggest hits were Airport and Love Story.

As iconoclastic as M*A*S*H is, its army medics and surgeons have one major inheritance from Old Hollywood: the unspoken camaraderie and flippancy towards death of classic Howard Hawks heroes.

No relation to the current production company Lionsgate.

Cannon’s ridiculous overuse of ALL CAPS makes his article read like the seventies equivalent of an angry 3 AM tweet.

Keep up the great work. Altman is under appreciated.

Love it. Thanks. For someone who has taken classes and later taught classes on Altman, this is music to my ears. His importance lies in the way he transformed cinematic storytelling, leaving a lasting influence on both filmmakers and audiences.