Altmanesque V

Nashville and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson

Thompson: Do you see a connection between what you do in films and painting?

Altman: I compare myself more to a muralist. The first thing I have to know is how big is the wall I have to paint? Is it a little wall or is it seventy feet high? And what is the subject? Even Diego Rivera had to be told that, although he wouldn’t do it the way they wanted.

Altman on Altman, edited by David Thompson

Parts one, two, three and four of this series.

Criterion Collection directed by Robert Altman retrospective.

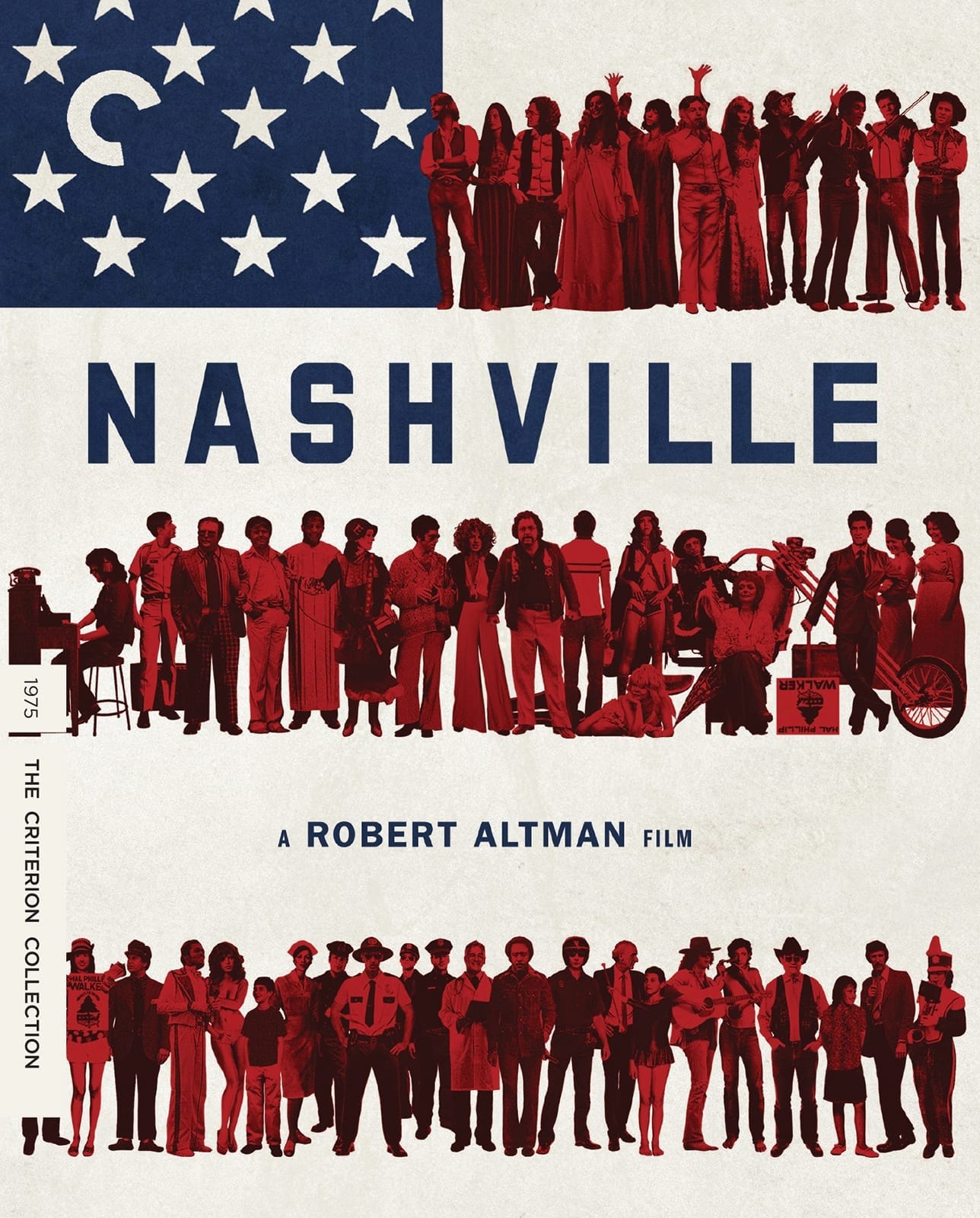

Nashville (1975)

I’ll cut to the chase here. If you can only watch one film from Robert Altman’s filmography, watch Nashville. Not because it’s necessarily his best or greatest film, although it has a strong claim to that title, but because it’s the most Altmanesque: the fullest expression of his idiosyncratic creative vision, the single film that best exemplifies Criterion’s description of Altman’s films as “worlds unto themselves, teeming with more humanity than a single story can contain.” This is a movie that could have only been made by Robert Altman & company in the year leading up to the 1976 American Bicentennial.

1975, as I mentioned in my piece on Jaws, is the best Best Picture lineup in Oscars history, a five-way heavyweight bout between all-timers. And Altman is up there, nominated for Best Director alongside Fellini, Forman, Kubrick and Lumet, with a cinematic accomplishment as enduring as Jaws or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Barry Lyndon or Dog Day Afternoon.

As with many Altman projects, Nashville began as one thing and then developed into something very different. United Artists, which had recently diversified by buying a country music publishing company, approached Altman to direct a synergistic country music movie. Altman in turn hired Thieves Like Us (1974) screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury and sent her to Nashville, the Mecca of country music, to find inspiration by soaking in its local color. Tewkesbury’s diary of her time in Nashville formed the basis for a much more ambitious, complex project that United Artists executive David Picker turned down.

Fortunately, Altman attracted the interest of superstar music manager and concert promoter Jerry Weintraub, who had ambitions of becoming a movie producer. Altman sold him on the project, which turned out to be a successful gamble: a $10 million gross on a $2.2 million budget, five Oscar nominations, and the beginning of a decades-long cinematic career that would see Weintraub produce the Karate Kid and Ocean’s Eleven trilogies.

“How would you describe the subject of the film?” David Thompson asks Robert Altman in Altman on Altman. “It was about the incredible ambition of those guys getting off the bus with a guitar every day,” Atman responds.

Like in Hollywood, trying to make it. Nashville was where you went to make it in country-and-western music. I just wanted to take the literature of country music, which is very, very simple, basic stuff — ‘for the sake of the children, we must say goodbye’ — and put it into a panorama which reflected American and its politics.

In the words of Pauline Kael, Nashville would be the ultimate Altman movie, the culmination of his work as a filmmaker up to that point. A quintessentially Altmanesque film about a community of people, made by a community of filmmakers and actors. M*A*S*H (1970) was about an army base in Korea; McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) surrounded its title characters with a western frontier town; Nashville follows no fewer than 24 characters over five days in Nashville, where they pursue dreams of country music stardom, become romantically entangled with each other, perform at various venues, and, in one case, act out darker desires. There is no central plotline; the plot, such as it is, involves the overlapping lives of these 24 characters.

Tewkesbury meticulously plotted the film’s narrative, planning each character’s activities and whereabouts for each fictional day to ensure that no one character would be offscreen long enough to be forgotten by the audience. Nonetheless, her plot structure left plenty of opportunities for actorly improvisation, as well as a few entirely improvised scenes inspired by particularly cinematic locations happened upon during production. In his Criterion director’s commentary,1 Altman describes his approach to making Nashville as “creating the event and documenting it;” he praises cinematographer Paul Lohmann for adopting a documentary approach to record spontaneous, unplanned action.

For instance, one of the film’s key plots involves the populist third party presidential candidate Hal Phillip Walker. Walker never appears on screen, but his campaign is a major presence in the film, via both his campaign manager (Michael Murphy), who attempts to recruit various country music stars to endorse the campaign, and his campaign van, which drives around the city of Nashville blasting slogans on a loudspeaker. Altman assigned a small team to create Walker’s campaign and then “invade my movie;” they did so by showing up at shooting locations2 with their campaign van, photobombing in-universe news broadcasts, and putting up campaign posters in the backgrounds of various scenes.

All of the songs — musical performances take up approximately one hour of this 160-minute film — were written and performed by the cast.3 Performed live onscreen, supported by backing bands of Nashville pros also playing live, in a film with almost no ADR. Actor Keith Carradine, who plays folk singer-songwriter Tom Frank, won the film’s only Oscar: Best Original Song for “I’m Easy,” a Billboard top 40 hit that topped the Easy Listening chart in the real world.

The technical glitches with multitrack sound recording on earlier Altman films were completely resolved on Nashville, enabling the sound team to mic every actor and mix their overlap dialogue and singing into a soundscape that somehow combines clarity of dialogue with the sensory overload of a crowded concert venue or city street.4

If you’ve ever worked on a film yourself, the production of Nashville might sound like an absolute nightmare, a chaotic situation that combines all the challenges of making a fiction film with all the challenges of making a documentary. But Nashville is a film where all these risks pay off. I’ve previously compared Altman’s creative process to jam bands; Nashville is the cinematic equivalent of the lightning in a bottle moments celebrated by Deadheads, where all the musicians seem psychically connected as they take the song in new, unexpected, fascinating directions.

In a 1975 Film Comment interview, actress Geraldine Chaplin told critic Jonathan Rosenbaum that “I’ve never worked on a happier film, ever.” In Chaplin’s words,

We used to see the rushes—two hours every day, and everyone came, had a drink, had a joint, and watched the rushes. It was like seeing a movie because everyone would laugh and applaud. And Bob would sit at the back like a great pasha and Big Daddy, and watch over everyone . . . There were so many good things that got cut out!5

Reviews of Nashville almost invariable provide a sentence-length run-on paragraph with pithy descriptions of each character. Filmsite.org provides a handy chart listing each character’s name, actor/actress and role in the story, supplemented by another chart connecting various characters to their real-life inspirations in classic country.

Instead of replicating these lists of characters, or trying to list all the moments that stood out to me (which would involve a blow-by-blow of large portions of the film), I’ll focus on one specific scene that brought me almost to tears.

About halfway through both the film’s runtime and its fictional chronology, we see a montage of four Sunday morning church services: Catholic, Black Baptist, White Protestant and the nondenominational hospital chapel where damaged, unstable country star Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakely) sings a gospel song from her wheelchair to associates, hangers-on and hospital staff.

Why did this moment affect me so much? I can think of three main reasons:

It presents a new side of characters that we’ve previously seen in very different contexts, placing them in a communal context and hinting at rich, unseen inner lives.

It offers a multiracial, literally ecumenical vision of American religion.

It grounds a movie about American music – not just country but also folk and gospel – in worship music, a taproot for almost every American musical genre.

And, of course, because it says something with sound and image that cannot be said in words.

“What this movie is about,” Tewkesbury would later tell Janet Maslin, “is making you draw your own conclusions.” Nashville is a narratively and thematically complex film that you should probably watch more than once, first to just experience the wave washing over you and then to find patterns. And it’s an open-ended film, one that challenges an active, imaginative viewer to create his or her own meaning. If you read Reddit discussions of Nashville, for instance, you’ll see very different ideas about how to interpret the final scene.

Indeed, the film itself seems to mock the idea of a simple takeaway message via Chaplin’s character Opal, a self-described BBC reporter who interviews other characters, alienating them with culturally and racially insensitive comments and with glib attempts to identify what everything around them means. One of the film’s funniest scenes – unscripted and completely improvised by Chaplin – features just her, wandering down rows of parked school buses, free-associating about what the color yellow represents in the psyches of American schoolchildren.

When discussing the film, critics and filmmakers tend to compare it to other, non-cinematic experiences, beginning with Altman himself and Nashville as a panorama of America and its politics.6 “Easy analogies,” Charles Champlin writes in his 1975 Los Angeles Times review, “are to the dense and teeming canvases of Breughel, to Hogarth’s serial vision of London, to the picaresque early English novels, to Joyce’s Ulysses as it immortalized a day in Dublin, to John Dos Passos’s ranging view of America in U.S.A.” Nashville is Joycean; Whitmanesque; carnivalesque; a panorama; a mosaic; a “massive, multi-textured tapestry;” a universe; a microcosm; a circus procession; An Altmanesque state of the union address; a time capsule; a “Chaucerian musical pilgrimage whose Canterbury is Nashville,” an “opéra comique – with tragedy;” an ecological system; a “catalog of loves, hates, ambitions, fears, nobilities and meannesses;” a “kaleidoscope of music, religion, and politics.”

Let me add a few more. Nashville is, in addition to everything else, a travelogue, a guided tour of Nashville, taking the viewer from the airport to the Grand Ol Opry, Opryland, a performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the life-size replica of the Parthenon at Centennial Park. It is, in hindsight, a testament to New Hollywood, which funded this audacious film, and to the American moviegoer, who made it a major financial success. And, fifty years later, it remains an accurate, prescient mirror of the United States, sincere and satirical, a film about media, celebrity, populist politics and their interconnections, about the American dream of creativity and personal reinvention and the American nightmare of public gun violence.

“This is a film about America,” the late Roger Ebert wrote in 1975. “It deals with our myths, our hungers, our ambitions, and our sense of self. It knows how we talk and how we behave, and it doesn’t flatter us but it does love us.”

Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976)

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846-1917) is a singular figure in American history. A relentlessly self-mythologizing former cavalryman and scout who served in the American Civil War and Indian Wars, Buffalo Bill established and starred in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a touring show featuring trick riding, horse races, music, dramatized reenactments of western history and appearances from iconic wild west figures like Annie Oakley, Calamity Jane and Chief Sitting Bull.

The mass appeal of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West made Buffalo Bill arguably the first modern global celebrity. International tours took him from the court of Queen Victoria to the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle to a personal meeting with Pope Leo XIII. And to the birth of cinema, including a starring role in an 1894 Edison film, the formation of his own production company, and a film career that lasted more than two decades.

A visionary showman, entrepreneur and performer who codified the western as a genre of entertainment; a Freemason; an early movie star; a tireless bullshitter who crafted a larger-than-life public persona; a feminist who argued for women’s suffrage and equal pay and practiced what he preached as an employer; a white man who fought and exploited Native Americans and yet was described as “a warm and lasting friend” by the Oglala Sioux tribal council upon his death. Buffalo Bill left behind a complex, contradictory legacy, one that seems tailor-made for cinema.7

In Robert Altman’s words, “our version was really about the beginnings of show business.”

Funded by Italian-American super-producer Dino De Laurentiis and featuring Altman — for the first time — as the credited director, producer and co-screenwriter, Buffalo Bill was the most expensive Altman movie to date. Its star-studded cast features Paul Newman as Buffalo Bill, Geraldine Chaplin as Annie Oakley and Burt Lancaster as journalist/dime novelist Ned Buntline, with Harvey Keitel, Shelley Duvall, Joel Grey and Will Sampson in supporting roles. It was shot on location at the Stoney Nakoda First Nation in Alberta, Canada, where production designer Tony Masters built a life-sized replica of Cody’s compound; Stoney Nakoda chief Frank Kaquitts (Sitting Wind) plays Sitting Bull in the film.

And it flopped. A deconstruction of American myth was the wrong movie at the wrong time during American’s Bicentennial celebrations. Altman declined the Golden Bear at the 26th Berlin International Film Festival to protest De Laurentiis’s cuts to the film; he would be fired from Laurentiis’s next project, an adaptation of E.L. Doctorow’s 1975 novel Ragtime,8 and forced to start over with lower budgets at Fox.

In the context of Altman’s filmography, Buffalo Bill does seem, in some ways, like a spiritual sequel/prequel to Nashville: another meandering, episodic film about a large ensemble of performers, another quintessentially American cultural phenomenon as a microcosm of America itself.

Nashville, however, is an open-ended film that offers a complex web of characters and ideas and challenges an active viewer to find his or her own meaning in it. Buffalo Bill, on the other hand, has a clear central thesis that even the most distracted of iPhone-wielding viewers would pick up on — that Buffalo Bill is a buffoonish, drunk fake hero profiting off of a falsified version of American history.

For all his problematic aspects, Cody was a kind of genius, a prototype for Walt Disney or Hollywood moguls who had his finger on the pulse of the American and European publics. He must have had some incredible inner hunger for fame and status, which drove him to create a new form of entertainment and tour it across multiple countries. While Newman is the spitting image of Cody on screen, you don’t get those aspects from his performance or from how the character is written.

Similarly, Sitting Bull was a complex, important historical figure who only gets represented as a passive, morally righteous victim; Sitting Bull the powerful military commander who defeated Custer at Little Bighorn and Sitting Bull the charismatic leader of Native American resistance movements are both absent from this film. There is an incredible film to be made about the relationship between Cody and Sitting Bull, and what that says about American history and culture. I don’t think Altman really made that movie.9

“I think Buffalo Bill is a victim, more so than Sitting Bull,” Altman tells David Thomson in Altman on Altman. Indeed, the last act of the film — which begins with Cody learning of Sitting Bull’s death — focuses on the character’s isolation and self-loathing, culminating with a drunken, Macbeth-esque encounter with Sitting Bull’s invisible ghost that, unfortunately, feels very actors’ workshop improv.

My mind goes to one of the quintessential 21st century westerns/revisionist westerns, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), which ends with Robert Ford cashing in on his notoriety by reenacting his killing of Jesse James for paying audiences. That is a film that tackles many of the same ideas as Buffalo Bill — the porous boundary between old west history and old west legend and the role of early celebrity culture in blurring that boundary — in a more effective, compelling way.

The Altman modus operandi is inherently risky: going off-script, encouraging actors to improvise, putting dozens of people together in group scenes and hoping that magic will emerge out of the chaos and that stringing together those magic moments will create something compelling in the editing process. Sometimes, those happy accidents just don’t happen, for whatever reason.

Buffalo Bill has a dream cast. I’ve seen pretty much every name member of its ensemble give at least one great performance in another movie. But it never catches fire, or takes flight, or comes to life — whatever metaphor you want to use. A collection of great actors, in period costume, on elaborate sets, who just don’t combine to create a fascinating Altmanesque world on screen.

There are some compelling moments, such as Sitting Bull’s onstage debut. On display for booing spectators like a zoo animal, he wins over the crowd with his quiet dignity as a surprised Cody peeks through the canvas to see what the cheering is about. Near the end of the film, the reception for President Grover Cleveland is vintage Altmanesque, juxtaposing an audience entranced by a visiting opera singer’s performance and a confrontation between Sitting Bull’s representative and Cleveland over broken treaties in a complex, thematically rich scene. A few aspects of Buffalo Bill — the similarity of Cody’s compound to a Hollywood backlot, the contract negotiations with Sitting Bull’s representative, which feel very insider baseball — point to this film’s potential as a precursor to Altman’s comeback with The Player (1992), to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show as a satirical metaphor for Hollywood artificiality.

Much of the film, however, just lacks narrative momentum. Part of it probably has to do with the single setting, and the large percentage of runtime devoted to preparing for and putting on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performances. Part of it is the lack of focus from a well-funded filmmaker with dozens of pieces on the board at the same time. Part of it is that a better Robert Altman movie about Buffalo Bill would lean into the obvious parallels between the two men.

While audio commentaries can be hit or miss, I’ve enjoyed Altman’s. They offer a wealth of interesting anecdotes about that particular film’s production, as well as some real insight into his unique approach to filmmaking.

The film was shot entirely on location in Nashville.

I can’t think of a better method acting exercise for playing a country music star than actually writing and performing country music.

In two fairly egregious snubs, Nashville was not nominated for either Best Sound or Best Film Editing.

While any actor or actress would be overshadowed by her famous father, Geraldine Chaplin carved out an incredible film career of her own, in multiple languages and multiple film industries, working with – among others — Altman, Carlos Saura, David Lean, Martin Scorsese, Jacques Rivette and Guy Maddin. From her father’s Limelight (1952) to Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018) and beyond, her filmography is worthy of its own Criterion Channel retrospective.

If you’re looking for cinematic comparisons, Kael makes two obvious ones in her 1975 review: Les Enfants du Paradis (1945), which I’ve previously discussed, and 8½ (1963). I’d add the early Altmanesque Paul Thomas Anderson films Boogie Nights (1997) and Magnolia (1999), as well as the kinds of international arthouse films critics call novelistic, movies like Amarcord (1973), The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978), A Brighter Summer Day (1991) and the early films of Jia Zhangke.

Roy Rogers, Joel McCrea, Louis Calhern and Charlton Heston played Buffalo Bill in movies before Paul Newman.

Miloš Forman replaced Altman in the director’s chair; the film came out in 1981.

My complaint, in other words, is not that the film is historically inaccurate, but that it’s historically inaccurate in ways that make the fictional Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull less interesting than the real historical figures.

timely post - i just watched nashville a few weeks ago. i couldn't agree more with the comparisons of the movie to a mosaic or a tapestry that Breughel could have put together.. given all the characters and plot points, there's just so much complexity to the movie - it's infinitely rewatchable

I remember watching both of these films, but even though I was in my late 20s, I was still too green to fully appreciate them. I remember thinking that Nashville was a really cool movie, but "Buffalo Bill" seemed to have no memorable identity beyond the great costumes. I didn't know who Altman was, or connect the two films even though the cast seems much the same.

Your writing is generous to the industry and the people in it. I hope you're collecting this work into some sort of book or library. I'll grant you that Substack itself fills that bill, but ... you know.