Altmanesque IX

Secret Honor and Fool For Love

This work is a fictional meditation concerning the character of and events in the history of Richard M. Nixon, who is impersonated in this film. The dramatist’s imagination has created some fictional events in an effort to illuminate the character of President Nixon. This film is not a work of history or a historical recreation. It is a work of fiction, using as a fictional character a real person, President Richard M. Nixon – in an attempt to understand.

Secret Honor opening title card

The series so far:

Altmanesque I: Introduction, Countdown, and That Cold Day in the Park

Altmanesque II: M*A*S*H and Brewster McCloud

Altmanesque III: McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images

Altmanesque IV: The Long Goodbye and California Split

Altmanesque V: Nashville and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson

Altmanesque VI: 3 Women and Quintet

Altmanesque VII: A Perfect Couple and Popeye

Altmanesque VIII: Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean and Streamers

Robert Altman on the Criterion Channel

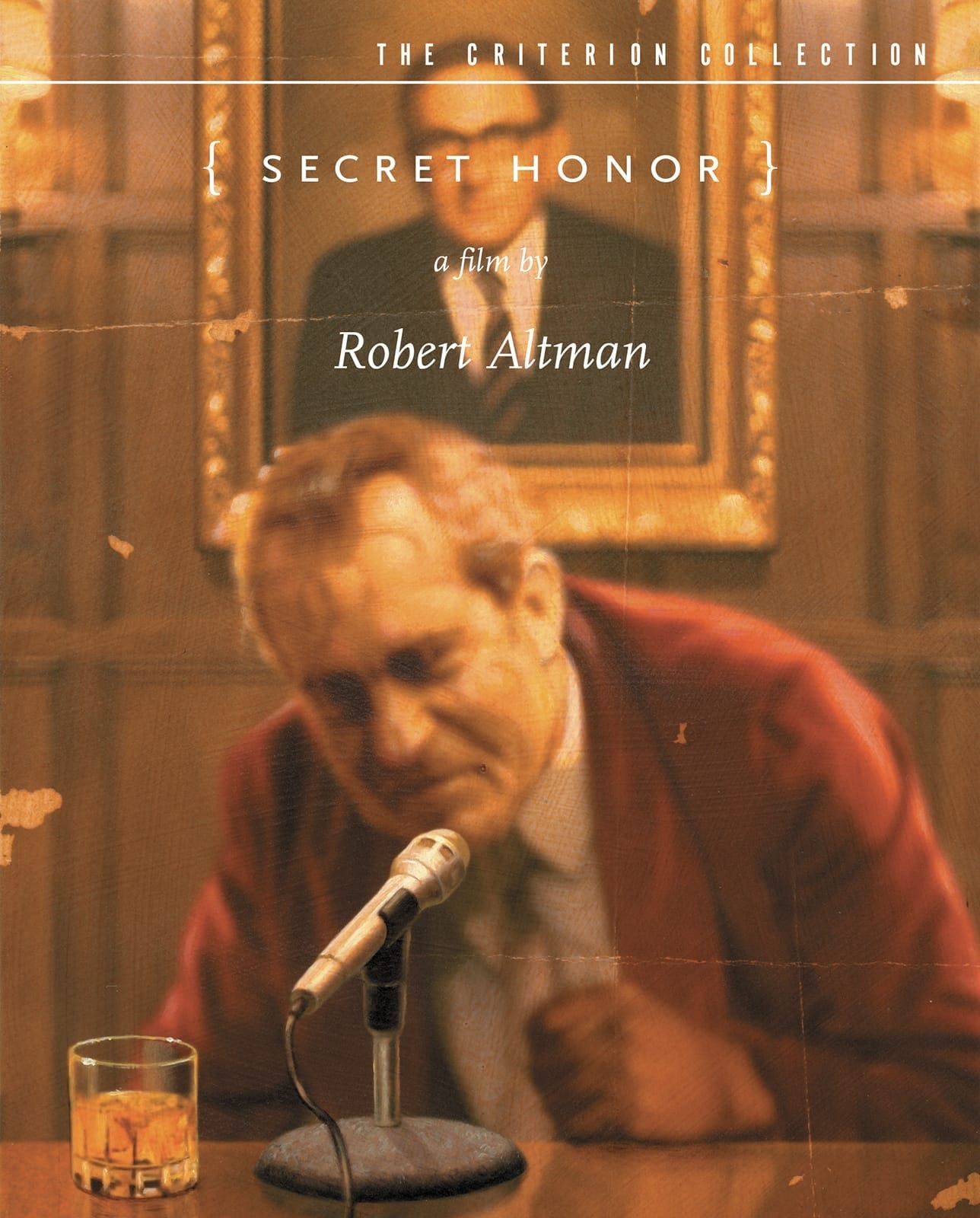

Secret Honor (1984)

Chaotic former child actor/living internet meme/bad music legend Corey Feldman crowned himself the “Comeback King” in a 2021 song. “Count me down,” he sings, “but you can’t count me out.”

If American cinema had an unironic Comeback King, it would be Robert Altman, whose filmography has more ups and downs than a rollercoaster and who found a way to somehow land on his feet after multiple critical and commercial failures. One of the jewels in that comeback crown is Secret Honor (1984), Altman’s best eighties film and possibly his most underrated, a film made on a shoestring during his exile from Hollywood that gets maximal results from minimal resources.

His previous project represented a career low point: O.C. and Stiggs (1987), a National Lampoon-inspired teen comedy that was shelved for years and made less than $30,000 during its limited release. In Altman’s words, “it was a suspect project from the beginning.”1 Work for a director in need of work. It is currently unavailable on any streaming service and thus will not be covered in this series.

Like the films I covered in the previous post, Secret Honor began on the stage: as the one-man show Secret Honor: The Last Testament of Richard M. Nixon, written by Donald Freed and Arnold M. Stone, directed by Robert Harders and starring the late Philip Baker Hall as Nixon. Altman saw the play in Los Angeles and produced it in New York (Off-Broadway) before bringing it to the University of Michigan, where he was teaching. Altman and a few key collaborators — including cinematographer Pierre Mignot and Altman’s son, art director Stephen Altman — oversaw a film adaptation of the play as a student project.2 As Altman describes it in Altman on Altman,

We made a course out of the production, and students had the opportunity to see what was happening on TV monitors in an adjacent hall linked to the camera in the ceiling of the room. Most of the crew were graduate students, and the dailies were open to everyone. The music was composed by one of the professors and played by the student orchestra. The success of the piece exceeded all my hopes, but even if it hadn’t, I believe it was a worthwhile project.

When you think of Altman and the Altmanesque, you think of, as Violet Lucca puts it, “cinematic plenitude: big ensemble casts, cascades of overlapping dialogue, loose and freewheeling narratives, and movies generously stuffed with more human detail than a single viewing can take in.”

Secret Honor is the exact opposite, a film about one man in a room talking. It makes sense as a student project because it’s about as logistically simple as a film can get. Stephen Altman transformed the front parlor of the University of Michigan’s Martha Cook building — a women’s dormitory — into Nixon’s study, adding the presidential portraits on the wall and various props (a gun, a glass of Scotch, a microphone) that Hall’s Nixon interacts with. We never leave that room.

One of my cinematic pet peeves is the use of heavy prosthetic makeup to transform an actor or actress into a Madame Tussaud waxwork of the historical figure they play. I generally find it distracting; I generally find myself wishing that the actor or actress could convince me through their performance and not by visual resemblance.

In Secret Honor, Philip Baker Hall is not a dead ringer for Richard Nixon. He does not wear heavy makeup to make him visually resemble Nixon, and he does not affect a Nixon voice. Instead, he uses the expressive power of his own face and voice to command the screen as a convincing, non-caricatured Nixon. Roger Ebert hits the nail on the head: “this is not an impersonation, it’s a performance.”

And what a performance it is. It has to be, because this is one of the rare films that is a literal one-man show. Altman took no credit for Hall’s performance. In his words, “He developed his performance with Bob Harders. They worked on it together for a long time, and it really had nothing to do with me.” Sometimes the best creative decision is to not interfere, to not fix what isn’t broken.

As Ebert puts it, Hall’s Nixon has “such savage intensity, such passion, such venom, such scandal, that we cannot turn away.”

He drinks Scotch, curses, laughs, shouts, spouts racial slurs, drinks more Scotch, reminisces about his middle-class Quaker childhood, expresses remorse, expresses no remorse, brags about his success, justifies his actions, indulges in self-pity, plays his own defense attorney, oscillates from manic energy to deep despair, jumps on the piano to play and sing a little ditty about “atheistic godless spying reds lurking under Democratic beds,” complains about his brother cashing in on his fame with Nixon Burgers, puts a gun to his head and spews a limitless stream of bile at enemies and perceives enemies: at the portrait of Henry Kissinger, who he calls “kiss-ass;” at the photogenic, charismatic John F. Kennedy who beat him in 1960; at the east coast Ivy League political establishment that made him feel like a constant outsider; at what we might now call the deep state that, he claims, really runs things.3

It’s a physical, demanding performance that was a grueling experience for Hall. In his words:

“Altman would do a take. Then he’d say, ‘That’s good. Want to do it again?’ I’d say, ‘I’m pretty tired.’ He’d say, ‘OK, let’s do another one.’ And we did long takes: fifteen, eighteen minutes—which in movies are unbelievable. Then he’d say, ‘You want to do another? Let’s do another.’ I normally weigh about 160 pounds; during the Nixon thing I went down to 127.”

Early in the film, Nixon recalls playing Hamlet in his younger years; Altman would later describe Hall’s performance as Shakepearean. As Nick Pinkerton notes, the idea of Nixon’s rise and fall as a Shakespearean tragedy is something of a cliché, especially comparisons of Nixon to Richard III. But Altman, no fan of Nixon, had what Pinkerton calls the “creative compassion” to present a sympathetic Nixon. Not a one-dimensional villain but a tragicomic antihero, not an American Richard III but perhaps something of an American Macbeth in a film that’s a bit like a very extended version of the “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy.

While Altman did not interfere with Hall’s performance, he did make two important creative decisions that make Secret Honor an effective film and not just a filmed theatrical performance.

First, through cinematography. Altman “had to devise a fluid way of filming it so that it didn’t look like a stationary camera with a single actor in a single room,” Hall told the AV Club in a 2012 interview.

So he happened to own this camera that’s like… it’s almost like an airplane. It’s on a big pedestal, about 8 or 9 feet high, and stands in the middle of the set, and it has a basket on it. And the cameraman, he’s in that basket and he has controls there. He can almost fly it like an airplane. He can go up and down and around.

…If you’ve seen the film or if you watch the film thinking about that, he was able to get a lot of very flowing, fluid camera movement around the action of that single actor without it looking like a fixed tripod in the middle of the room, with lots of stops and starts. So we were able to do very, very long takes. Fifteen- or 20-minute takes with that particular camera set-up. It was really interesting. That’s really what he brought to it: a way of filming it.

Second, through mise-en-scène, as Altman and his team made critical decisions about what that fluid camera records. As previously mentioned, Stephen Altman dressed the set with presidential portraits, including Dwight Eisenhower, Woodrow Wilson and Abraham Lincoln; Nixon’s dark night of the soul literally plays out against a backdrop of American history. Even more important was the decision to add security cameras and monitors to the microphone and tape recorder that Nixon uses to record his stream-of-conscious thoughts.

“I think they saved the film,” Altman recalls in Altman on Altman.

The big problem was that a one-man play gave me no cutaways, so what was I going to cut to if I wanted to truncate it, eliminate pieces of dialogue or just not be bored? The students at Michigan set up these monitors for me, and that proved a real good solution. I like the bad quality of the image; it almost gave the impression we were watching old films of Nixon’s television appearances.

That last sentence is key because blurry-black-and white television monitors take on an iconographical significance in the context of Nixon’s career. Most obviously, the combination of microphone, tape recorder, security cameras and monitors signify surveillance and evoke Watergate and the notorious Nixon tapes. To borrow a phrase from T.S. Eliot, they serve as objective correlatives to Nixon’s inner paranoia.

As Altman notes, they also evoke the iconic moments of a political career that unfolded, to a great extent, on television. Americans saw Nixon deliver his Checkers speech and debate JFK on small, grainy black-and-white television screens. Secret Honor is a chamber piece, not a biopic, but these moments — combined with the portraits of presidents and Kissinger — wordlessly evoke both Nixon’s career and the broader historical context.

Finally, the addition of security cameras and monitors leads to a strange, thematically resonant ending. The camera pans and zooms to reveal a bank of four monitors with four black-and-white Nixons raising four defiant fists into the air and shouting “fuck ‘em!” It pans across the monitors again and again, looping the same moment over and over and over. It’s a moment that reminds me of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen images of celebrities and, like them, suggests that Richard Nixon is also an endlessly reproduced icon in an age of mechanical reproduction.

Secret Honor earned Altman his best reviews since the seventies, with raves from Ebert, Siskel, Vincent Canby and others. As a low-budget, originally noncommercial project, it got a very limited theatrical release but found a new audience when the Criterion Collection released it on DVD in 2004.

Secret Honor did have one major impact on film history, and certainly on the life and career of Philip Baker Hall. The critical acclaim for his performance led to new career opportunities, new roles in film and television. It also piqued the interest of a young cinephile and Altman fan named Paul Thomas Anderson. While working as a production assistant on a PBS tv movie starring Hall, Anderson asked Hall about working with Altman and shared a short film script with him. Hall starred in that short film, Cigarettes & Coffee (1993), and reprised the role in the expanded feature film version, Anderson’s debut Hard Eight (1996). Hall’s roles in that film, Boogie Nights (1997) and Magnolia (1999) catalyzed a well-deserved late career renaissance as a Hollywood character actor.

But Secret Honor might be his best performance: a bitter, cathartic, conflicted airing of grievances that does succeed — at least artistically — in its attempt to understand.

Fool for Love (1985)4

While Altman’s three stage-to-screen adaptations weren’t exactly blockbusters, they did open doors. After two other film projects fell through, Altman reached out to playwright-actor Sam Shepard — who had previously collaborated with Wim Wenders on Paris, Texas (1984) — about adapting his 1983 play Fool for Love into a film.

Altman had also landed on the radar of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus’s Cannon Films, which produced the Akira Kurosawa adaptation Runaway Train (1985) that I covered in a post last year. Cannon Films is probably best remembered for kitschy, sometimes cult classic genre movies: Death Wish sequels; Lou Ferrigno Hercules movies; Chuck Norris vehicles; Breakin’ (1984) and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984); Lifeforce (1985); Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987); Masters of the Universe (1987). However, they also demonstrated a willingness to bet on risky auteur projects; John Cassavetes’s Love Streams (1984) and Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear (1987) were also Cannon Films, as was Fool for Love.

The larger budget led to bigger names in the cast. Sam Shepard himself and Kim Basigner as the two leads, alongside Harry Dean Stanton as the unnamed Old Man and Randy Quaid in a supporting role. It also led to a much larger physical setting than Altman’s three previous stage-to-screen adaptations. Stephen Altman’s production design team built a complex of roadside motel cottages and junked cars near Santa Fe, New Mexico; it’s a perfect example of invisible production design, production design that creates the illusion of a real, lived-in location.

This bigger scale is apparent during the film’s very first shot, which provides a striking contrast to the claustrophobic Secret Honor. The camera pans across the New Mexico landscape and then begins a trademark Altman slow zoom to a trailer in the middle of a junkyard behind a roadside motel in the middle of nowhere. The trailer door opens. Stanton’s Old Man walks out and begins playing the harmonica. It’s an establishing shot that immediately establishes a sense of isolation and sense of offbeat, somewhat laidback strangeness.

Unlike previous stage adaptations, Altman opened up Fool for Love through the elaborate open-air set and through translating character monologues about their pasts into flashbacks with voiceover. This allows for a series of vivid visual details, especially in the first half: a rusted, mud-splattered white truck; weathered adobe and stucco walls; the glow of the motel’s neon sign against a dusky sky. At times, the desert atmosphere recalls the eeriness of 3 Women (1977).

In a 1997 Paris Review interview, Shepard expressed “mixed feelings” about Fool for Love.

Part of me looks at Fool for Love and says, This is great, and part of me says, This is really corny. This is a quasirealistic melodrama. It’s still not satisfying; I don’t think the play really found itself.

I’m not sure the film really found itself either, and I think the casting might have been an issue. Jessica Lange5 was originally cast as May but dropped out due to pregnancy and was replaced by Kim Basinger. Altman replaced Ed Harris, who played Eddie on stage, with Shepard himself; Shepard would later criticize this decision and describe himself as too close to the material to do it justice as an actor.

Describing a film as sagging in the middle is a really overused reviewer’s cliché, but the second act of Fool for Love — which, for the most part involves Basinger and Shepard’s ex-lovers arguing in the motel — might actually fit that description. Perhaps a different actor, actress or both would have brought something different to the table.

Equally, a director more willing to reimagine or even deviate from the source material — the film is a very close adaptation — might have found a way to turn a decent film into a very good one. Altman’s Fool for Love unfolds in a realistic, lived-in setting; perhaps a director with a more surreal or gothic sensibility would have been a better fit.

Fool for Love does pick up in its last act, when the presence of Randy Quaid’s interloper ramps up the tension and pushes the three main characters to reveal their dark family secrets. It becomes an entertaining southern gothic melodrama and interesting exploration of the title: how, as Emily Dickinson put it, “the heart wants what it wants,” how falling in love can lead to foolish, irrational, even unethical decisions. It ends with a conflagration and a memorable final shot of Harry Dean Stanton playing his harmonica as everything around him burns. (If we ever get tired of the this is fine meme, I propose this a GIF or JPEG of this shot as its replacement.)

Fool for Love received generally positive reviews. While it only cost about $2 million, it made less than $1 million during its limited release. In other words, another flop. Altman the cinematic comeback king was down again, but not out.

Altman on Altman, edited by David Thompson. As always, this is my primary source for quotes and background information.

If you know of another example of a student film/student project that went on to become something of a minor classic, please let me know in the comments.

The title comes from a moment late in the film when Nixon describes his “secret honor and public shame” in the aftermath of Watergate, which he claims was an orchestrated set up, with him as the fall guy, to conceal a deeper conspiracy.

You can watch Fool for Love on Tubi, Amazon Prime or MGM+.

Shepard’s long-time romantic partner.